My friend CP is angry about the tariffs, which concerns me as a long-term protectionist. Ever since reading Pat Buchanan’s The Great Betrayal in college, I’ve been convinced of the case for tariffs and protecting domestic industries. Buchanan convinced me, against my Jeffersonian biases, that the Yankees were correct and Republican Party policies to build domestic industry during the 1800s were both right and necessary if the United States were to develop into a proper nation with real sovereignty1.

My friend’s primary argument is that Trump’s tariffs seem contradictory in their purposes. If they are opening positions subject to negotiation, then no one will invest in domestic manufacturing, knowing they are likely to be rolled back. If they are meant to be permanent, their broad nature doesn’t seem to make sense. Do we want to have sweatshops making stuffed animals in our advanced economy, or is it better for this to be done in Vietnam?

Thoughts:

I don’t see Trump’s position as necessarily contradictory but rather irrational for a purpose. Other countries do in fact place tariffs or play other games to harm US exports, and to the extent they do, this harms domestic industries. Long-term, economists would argue these countries are only hurting themselves, but the medium-term consequence in a democratic system is a loss of the kinds of jobs that create good incomes for the majority of people who work with their hands. I question the value of many white-collar jobs but suffice it to say that for the average person, machine-assisted manufacturing is the best way for them to produce sufficient economic value to support a family. If the result is a renegotiation of trade agreements to be less punitive to US exporters, this may have something like 25% of the effect of a long-term tariff program, with more immediate benefits and less dislocation in the economy. I suspect this is likely the case given the limits of a democratic society to stick to a long-term strategy. Unlike the Chinese, our democratically elected leaders are renters, not owners, of political power and cannot successfully execute a multi-decade plan to reindustrialize. Since they know that we know this, Trump is most likely doing his crazy act to seem irrationally tied to the proposal no matter the consequences, as documented in his master class in brinksmanship in The Art of the Deal. Since he may have to stick to the crazy act for a time to demonstrate his commitment, it’s smart to do this as early as possible in his term.

CP makes a compelling argument from the perspective of cornucopian economics that it makes sense that advanced economies will evolve away from manufacturing to value-added services. We design iPhones instead of manufacturing them. I am extremely suspicious that a sustainable economy is built on email jobs, and that long-term trading partners will be content for US companies to capture the intangible part of the value chain. The race to the bottom for Chinese no-name brands on Amazon, for example, shows consumers, in most industries, don’t care that much about quality or design. I also question whether the distribution of income in such an economy is politically sustainable or highly desirable. I think CP might agree that China is a problem and should be targeted but rather objects more to the blunt, worldwide nature of the tariffs, and the political consequences for other conservative priorities if this tanks the economy.

My biggest uncertainty is whether I’m right about the necessity of manufacturing as the foundation of an economy. A lot of conservatives were similarly dead wrong in the 1800s about agriculture, with a lot of political capital invested in hare-brained schemes like silver-based inflation. Recall William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech in which he compared the plight of farmers paying back mortgages in gold-backed dollars to the sufferings of Christ. Bryan and his farmer supporters wanted to devalue the currency to relieve the debt load of a sector destined to fail as science increased crop yields and sank crop prices. Many a prominent American family were impoverished2 by trying to hold onto the family farm for too long, romanticizing the Jeffersonian ideal of the politically independent gentleman farmer as the foundation of the republic. The crushing economics of cheaper food and consolidation meant that there was no possible political intervention to save the family farm, as now fewer than 1% of Americans grow all our food. Similarly, there’s an argument that manufacturing is doomed as well as a large source of employment, especially when it’s new, highly automated investments of the type that would be stimulated by tariffs. Hyundai, for example, recently announced a steel mill in Louisiana; their $5.8 billion investment will create a grand total of just 1,300 direct jobs.

However, if manufacturing was becoming obsolete as a source of quality employment, we would see manufactured goods getting a lot cheaper. This is only true in limited cases, especially electronics and trivial consumer goods. The former isn’t trivial at all and represents a huge increase in wealth worldwide, but seems more related to technological advances limited to the narrow but critical business of manipulating, transmitting, and displaying data. For things that involve atoms, from refrigeration to automobiles to homes we have not seen massive decreases in cost over time, or if we have they have come at the price of lower quality or fake “efficiency” improvements dictated by regulation. My air conditioner is more efficient, for example, because the government mandates I can only have the thinnest tubing which makes it fragile and prone to refrigerant leaks, and repairs and a shorter service life eat up the modest energy savings.

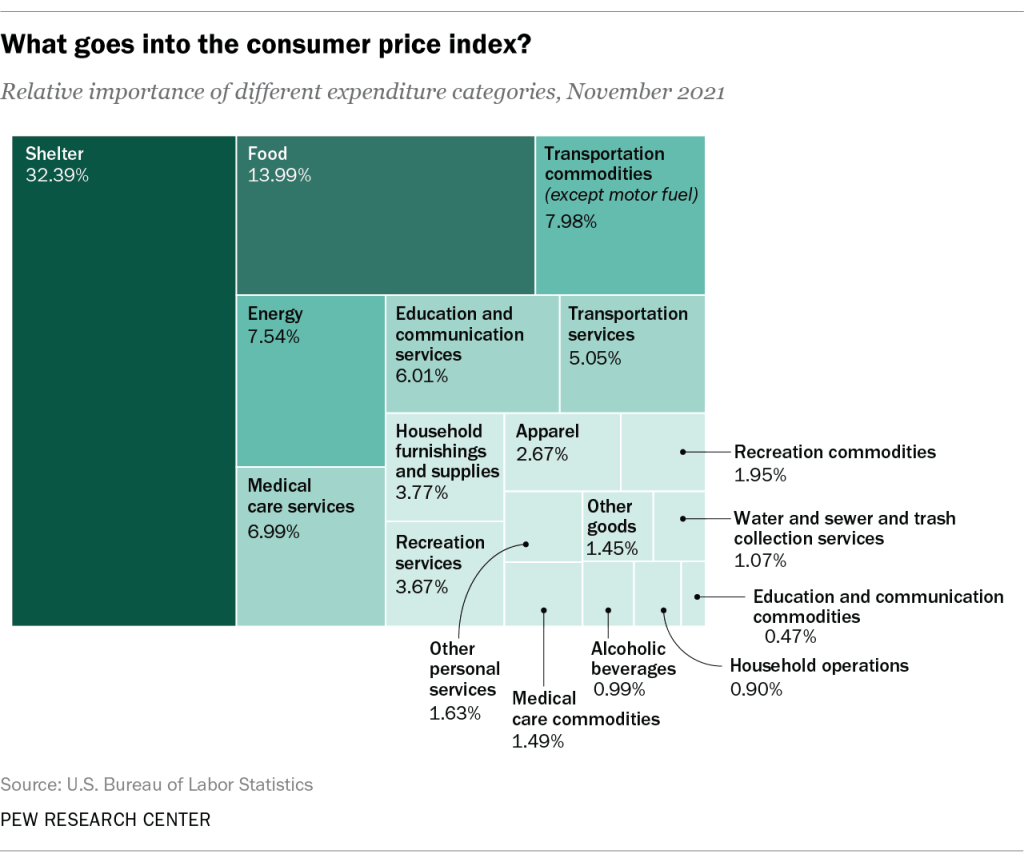

Looking at #4 a different way, most of the CPI is still goods, not services. We have not seen the cost of manufactured goods, notably, the components of housing and automobiles, fall to the same degree that food has after the agricultural revolution. And as I quantified in a recent column, if one looks at asset prices instead of rents, middle-class life is more unaffordable than ever. The arrival of true post-manufacturing cornucopianism would see the hard goods components falling to a much smaller share of average consumer spending, and services like travel and medical care accounting for the majority. In asking ChatGPT o1 to give an estimate, it appears that about 75% of today’s CPI involves an exchange of atoms or the use of atoms, versus 80% or so in 1980. Directionally, we are moving towards services, but not much over 45 years.

Thus, it seems, for now, that manufacturing remains a critical area of the economy, and innovation in manufacturing works best when manufacturing is conducted domestically. How can engineers follow the Japanese dictum of “go and see for yourself” on the production line when design and manufacturing are on different continents? There’s an argument that separating the two is a trade for short-term gains in profits at the expense of long-term innovation and value creation.

Further, I think there is an irrational bias towards outsourcing manufacturing. The fiat economy has elevated finance-oriented generalists rather than engineering types to the top of company hierarchies, and generalists find manufacturing tedious and boring, its problems impervious to verbal-tilted BS and slide decks. These personalities, whose economic value is based on perception, position, and pedigree, also largely loathe their fellow Americans who are blue-collar due to classism. Engineers are usually too autistic to care much about class, but finance bros certainly do. As I wrote in one of my unpublished works on business:

I also believe classism drives the outsourcing movement in business beyond its rational bounds. Long gone are the Horatio Alger-esque stories of people starting as a janitor at some large company and making it to the executive suite. Today, at nearly every major corporation, those services are outsourced to vendors whose employees will never have a similar opportunity to advance, often at a greater cost and certainly lower quality than internal employment.

Similarly, discomfort in interacting with blue-collar workers irrationally drives a preference to outsource to offshore production. If companies properly account for transportation and coordination costs, they often find it’s not all that expensive to manufacture many things in America. But, it requires management to deal with people who aren’t like them culturally, their brothers and sisters in their own country, instead of remaining in the white collar bubble and pushing all of the work they consider beneath them, outside of their “core competencies,” to far-away vendors whose workers, and working conditions, they never see.

We, however, agree with Marx (and Henry Ford, the great vertical integrator) that market power flows from owning, not renting, the means of production. During the Covid-19 crisis, we never missed a beat in manufacturing and shipping our products while competitors who did not have the same ability struggled with supply chain issues. We are willing to deal with the headaches and willing to get outside our bubble and see how our products are made, and take care of the people who make them.

I also reject the idea that Americans are too lazy and immoral to do manufacturing jobs. During the presidential campaign, news media featured a local manufacturer in Ohio who praised his cut-rate Haitian immigrant workforce for showing up to work and not being on drugs while taxpayers footed the bill for social services and education for the broader Haitian population locally. But dig a little deeper and check the company’s Indeed profile, and they’re paying welders $17 an hour, which I would consider a starting wage for an unskilled worker! My experience hiring in rural America is that it’s not that difficult to find good workers who are very happy to have a factory job, love the dignity of a workplace that isn’t directly serving retail customers, and enjoy a great sense of satisfaction from doing tangible work they can see, touch, and feel at the end of a long work day.

One problem in thinking about these issues is that the American worker has been attacked from two directions. We've never seen a world where we have both free trade and limited immigration. Technically, HVAC technicians, roofers, carpenters, etc, are services, but work with their hands, not unlike a manufacturing worker. Would we care as much about saving manufacturing if those guys had wages of $75 an hour and outearned most non-technical college graduates as they arguably should, given the relative utility of their respective skill sets? Our elites, however, weren’t content merely to ship most of their jobs off to China but also imported labor here to lower their wages in related tangible services. The lack of counterfactuals makes it difficult to analyze.

Overall, a more targeted approach would have been preferred by most and would certainly be more comfortable for those of us seeking to live on investment rents. And there are a lot of targets.

By way of example, why is India allowed to sell pharmaceuticals to the United States at any price? As a former employee of an FDA-regulated company, I remember how much of the regulatory burden to make safe and effective medical products relies on voluntary compliance and self-reporting. That was never a problem in the Georgia factory where I worked, as the extremely conscientious blonde lady in charge of our group’s QA had an almost religious devotion to her responsibilities to protect the public. But functionally, her job was just paperwork, and if one was willing to forge records and cover things up, the FDA wouldn’t ever know the difference. That seems like a bad bet in a country with insufficient social trust to execute universal basic sanitation!3 There are so many examples like this of specific trade problems that the universal tariff approach seems risky. But if I’m right about #1, and I think I am, a blunt approach may be the best way to handle as many problems as quickly as possible. Let’s not forget how many times we’ve underestimated the Orange Man previously.

In summary, I don’t know how the tariffs will work out, which seems a wise position for complex economic problems. I’ve often described my thinking process as having two lawyers in my head who argue with each other all day long. I’ll let the reader decide which side is more convincing.

Coda: Impact on Prices

I am more certain that the impact of tariffs on prices will be much less than their retail rates.

First, for trivial goods from China — plastic junk from Amazon — the vast majority of the price to consumer consists of fulfillment costs, which are not subject to the tariff. Perhaps you as a consumer thought you paid Amazon for free shipping by being a Prime member and that Amazon eats the shipping cost when you purchase a product from a seller. Wrong! You also pay Amazon for shipping each order through hidden fees charged to the seller for fulfillment.

This is why products that cost $1 to make in China cost $10 delivered to your home; most of that is Amazon’s fees and any advertising expense the seller has spent on the platform. When those products are imported, the tariff is on the cost of the good, so even at 80% your $10 junk delivered is worth $1 on the container ship and will cost at most 80 cents more, and that’s only if the seller (unlikely) has pricing power. To the extent the product is a no-name commodity, like so many things on Amazon, most if not all of the cost will come from the Chinese seller’s margin.

This, however, may be an even smaller problem. Since Amazon has managed to legally categorize itself as a mere marketplace, though they control all aspects of the customer relationship, the importer of record on all this plastic junk will be the Chinese factories. And our tariff enforcers rely on these factories, outside the reach of US criminal jurisdiction, to submit invoices honestly, under penalty of perjury no doubt, listing the cost of the products imported so they can be fairly taxed according to Anglo-Saxon norms of propriety! Many a Chinese importer will have no problem paying a few pennies of tariff on remarkably low cost of goods sold. They must think it’s very cute how we trust people to be honest in crafting paperwork!

Second, for non-trivial goods, where we have domestic producers, we undoubtedly have shadow capacity. And given the uncertainty of the tariffs and the stickiness of prices, most of these domestic producers will simply expand capacity instead of raising prices much. In my little operation, we could easily expand our average output by 75% with existing equipment, and the workers would be super pumped. Productivity would rise as fixed costs were spread across more units, and any idle wages paid would be eliminated by the pressure to get the order out by quitting time.

Some have similarly critiqued the tariffs on capital goods, i.e., the machines used to produce consumer goods, many of which are made in Europe. Again, the capital cost of equipment is a relatively trivial cost per unit of consumer goods. For us, it’s on the order of 2% of the price the customer pays. We’d happily pay a 20% tariff on our capital expenditures if we could sell even a tiny single-digit percentage more products into the market. And, most critically, like many producers, we have a choice between domestic and foreign producers of those capital goods, which means we might not even pay more.

Third, don’t discount the impact of domestic producers taking market share if the tariffs manage to last a few months. Once a customer switches, it’s hard to switch them back, and this is more true for higher-margin products with more differentiation which will tend to have more lock-in effects on the customer. I would expect many importers, especially those from mercantilist competitors like the Koreans or Europeans, to eat the tariffs, perhaps with their own government’s subsidies, to maintain their market share while working to move at least some production to the United States. And if this becomes the Nash equilibrium, and US prices don’t rise much overall, there will be even less political pressure on Trump to back down and more pressure for other countries to make a deal.

And it’s an interesting test of economic theory. Which is more powerful, the rest of the world’s quasi-monopoly, or the US’ quasi-monosopny?

One of my critiques of the Confederacy, leaving the slavery issue aside, is that it was essentially an agricultural economic system addicted to cheap labor and uninterested in the development of a true middle class and manufacturing might that would become self-evidently necessary for independent sovereignty in the great modern wars. It lost the first modern war largely for these reasons, and because it didn’t function as a nation, in that it was unwilling to make the sort of sacrifices necessary to win. Alexander Stephens, for example, the Confederate Vice President, spent most of the war sulking on his plantation carping about Jefferson Davis being a worse tyrant than Lincoln for enacting wartime measures like conscription that offended his Jeffersonian sensibilities about the proper role of a national government. Sam Houston, in opposing secession, warned the South of this, that they underestimated the North’s willingness to fight and overestimated the importance of a superior martial culture over the grim mathematics of industrial war capacity.

Their unwillingness to change meant that a lot of the emerging economic opportunities went to immigrants. In my little Faulknerian postage stamp of native soil in Louisiana’s Florida Parishes, many of the wealthiest families are of Italian descent, who immigrated for agricultural work post-war but quickly entered better businesses, lacking any romantic attachment to the land.

Given even generic drugs are worth more than gold per gram of active ingredient, labor savings cannot be the primary motivator, but rather the savings of a more “flexible” culture milieu and minimizing the chance of a “surprise” FDA inspection which rarely happens in overseas facilities. My former employer had an internal team that would show up and do surprise inspections, sometimes led by former FDA inspectors, to make sure we were ready for the real thing.

How do you reconcile the advancements in productivity? Although number of people employed in manufacturing has plummeted (1), real output has stayed about constant or gone up (2). That seems to suggest that returning to past levels of manufacturing employment would result in massive amounts of output—way beyond returning to prior levels of industrialization. Having a goal of returning to that level of manufacturing employment may be unrealistic.

1. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/manemp

2. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/OUTMS/

I vacillate between a) Trump is a retarded Boomer fighting the last war and b) politicians and the globalist capital classes arrayed against him won't negotiate in good faith for an equitable solution, hence he has to take the scorched-Earth approach with facially retarded self-imposed deadlines. I'm aware it could be both. Lol. I'm certain it's neither.

As far as pharma manufacturing, did you see our review of 'Bottle of Lies'? It is 100% regulatory arbitrage. Outrageous it was allowed to happen and indicative of the depth of evil and greed we are dealing with on the part of group b).

So yeah, maybe a targeted approach is impossible. Any instrument finer than a club to the head won't get the job done.