Last year, I published a modest piece of parenting advice on cultivating proper disgust and discretion in one’s children. In the intro to that piece, I wrote:

I’ve been loath to give parenting advice in these columns. Newlyweds shouldn’t give marital advice, and people whose children aren’t yet fully independent adults should be cautious about parenting advice. The problem with this is by the time parenting advice has credibility in terms of its outcomes — of course while acknowledging the role of factors outside of the parents’ control in outcomes — it is likely much of the advice is at least partly outdated in our fast-changing world.

Parenting in a world with smartphones is possibly more different than any world of parenting in the past. Those who grew up before 2000 might have more in common with a Roman adolescent’s experience than those growing up in the Panoptipercepticon of the AI-powered cloud and distributed mobile social media.

So with caution in mind, I will tempt the fates by occasionally writing what I will admit is “half-baked parenting advice.” Take it or leave it, there’s no warranty, strictly sold as-is, and may only be worth what you paid for it. These are simply some of the mental models I’ve found useful in making best guesses for parenting.

In this piece, I’ll again tempt fate in giving more of my half-baked thoughts on parenting.

Understanding the Primacy of Nature Is a Parenting Superpower

The economist Bryan Caplan published a book a few years ago encouraging people to have more kids. He cited the well-developed literature that genetics is most determinative for children’s outcomes, so parents should stop worrying so much about effort per child and have more children. And children are, strictly speaking, pretty cheap. In our post-scarcity world, you can feed them all essential nutrients with pork, sweet potatoes, rice, and beans for pennies a day, and that’s almost all that’s strictly required.

I endorse Caplan’s position, properly clarified. It’s not that nurture or parenting isn’t important per se. For people smart enough to read Bryan Caplan, certain environmental variables are operating in a very restricted range. The children of his readers will largely be loved, adequately fed, and live in a milieu of middle-class people who meet their responsibilities. Caplan’s point is that the marginal benefits of more intense parenting, once this base is assumed, are minimal (and perhaps negative, given the neurotic nature of many helicopter parents), so you’re better off having more kids than trying to optimize the childhoods of fewer of them. It does not follow that Elon’s approach, however, of creating fatherless children and betting purely on genetics, is likely to turn out as he expects, as such behavior is far outside of the range of environments implicitly assumed in the literature.

Practically, the best way to see children is not as blank slates but as undeveloped photographic film. The film can be developed poorly, but it cannot be developed beyond what is already there. And given a reasonable range of parental practices, notably love, two-parent households, etc, genetics come to predominate. As any parent can tell you, a child’s temperament and personality from the earliest ages are largely inborn, unalterable, and predictive of their eventual development. The most important “parenting” decision is who you choose to have children with, as each child is a remix of both parents’ dominant and recessive traits.

Recognizing that nature makes children different eases pressure on both the parent and the child, and helps avoid serious parenting mistakes that deprive children of love and can even lead to cruelty. Several of my children have been involved in running sports, perhaps the most genetically determinative of all sports, assuming some reasonable level of practice and conditioning. Yet I have observed many “sports dads,” under the illusion that “character” and “grit” are all that matter, yelling at their kids for failing to perform at a competition. Similarly, I have been told by overconfident tutors that “anyone” can learn advanced calculus if their specific techniques are followed. Kids who don’t measure up are blamed for character deficits by such parents, undermining the attachment that is critical to the relationship.

Thus, given the primacy of nature for both parents and kids, much of my advice will be negative, in terms of things to avoid and protect kids from assuming some sort of reasonable base of parental love, capability, and support, but this emphasis is simply practical. But the positive side cannot be overstated: children are a wonderful source of joy and fun. They make every life experience fresh and new, and the struggles of this life worth the effort.

On Behavior

Jordan Peterson explains the purpose of behavior training when he instructs parents to “do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them.” His point is not one of selfishness on the parents’ part, but rather an allowance for the parents’ bias! We tend to naturally like our children, so if they behave in ways that make us dislike them, other people will definitely dislike them, and preparing them for social life with other humans is a top priority.

Child behavior is more about consistency and quick delivery of some consequence, and mostly unrelated to mode1 or severity. Mostly, kids are impulsive, and much of this in the early years is simple operant conditioning. Overly talking about things is probably bad with children of any age, and delivering a reasonable, minor consequence consistently seems most important. Dr. Phelan’s 1-2-3 Magic is one approach that embraces this philosophy. Simple, but not easy.

One thing I’ve deliberately avoided is overly spiritualizing discipline. Many of the things kids do, again, are just impulsive, not big spiritual shortcomings. But one problem with the modern church is a tendency to overspiritualize everything, and that runs the gamut from the Duggar-aligned Pearls to more respectable voices like Paul Tripp. I’ve always felt intuitively that it borders on spiritual abuse to make every discussion about disobedience relate to the kid’s “heart” or whatever. Some children require more correction, and temperaments associated with this are evident almost from birth, well before a child is making conscious moral choices. Linking the child’s spiritual state to their unchosen temperament is thus a form of spiritual abuse.

And this, I think, is the biggest risk for naturally conservative, religious parents, particularly those in fundamentalist-adjacent communities. One big piece of wisdom my parents taught me was to be skeptical of anyone who “wears their religion on their sleeve.” Religion, unfortunately, can attract the mentally unstable, with the broader evangelical world full of incompetent Bible interpreters who extrapolate wisdom literature into rules-based systems they think provide guaranteed outcomes, not realizing the whole rickety edifice is speculation stacked on speculation. Many unintentional abuse situations come from parents attempting to use rigid frameworks despite observational evidence that it’s ineffective in this situation for this child.

Business experience has given me a natural allergy to overconfidence. I know how difficult it is to A/B test a website layout based on thousands of randomized trials with certainty. Hence, people who claim certainty with fewer samples on more complex phenomena like human behavior are usually wrong. While others’ frameworks can be useful, particularly those more evidence-based, children are so diverse in their temperaments that there’s no substitute for relying upon intuition based on personal observation.

Most behavior situations are not a spiritual crisis but are best handled with a quick, mild consequence and moving on with your day. It’s the endless talking about it that undermines the relationship, as most kids are willing to take the L on a consequence if the parent can avoid the temptation to lecture, and it’s consistent consequences, ideally ones that model real-life consequences as closely as possible, that change behavior. Again, simple but not easy. The parental fantasy of lectures, it seems, is that somehow the child will reach a state of enlightenment through argumentation: “Yes, Dad, I now see the error of my ways through your clear and cogent elucidation of moral principles, and I will correct my behavior going forward.” I like debates, so I find myself sucked into this more often than I should!

For older kids, a good resource is Kevin Leman’s New Kid by Friday. Leman is a Christian, but smartly avoids spiritual manipulation as a discipline strategy. Rather, he has the parent operate from a position of strength as the provider of things kids want, but don’t have to have. It’s a very Zen approach of asking calmly for compliance and delivering a natural consequence with minimal emotional engagement. Parents have more leverage than they realize, which is best exercised quietly, from a position of strength, rather than endless arguing and debate with someone who is not the parent’s peer and shouldn’t be treated as such. Kids are natural empiricists and understand quickly that talk is cheap.

On Teenagers

Chimpanzees make lovely pets until they hit puberty, at which point they can rip a human’s face off. So it’s not entirely unrelated to state that just as one should be cautious about taking marriage advice from newlyweds, one should be very cautious about taking parenting advice from those whose children have not yet entered and exited puberty with good outcomes. A huge parenting mistake is expecting linear progress in maturity based on age2.

I wrote the following summary on teenager psychology in my post on the Duggars:

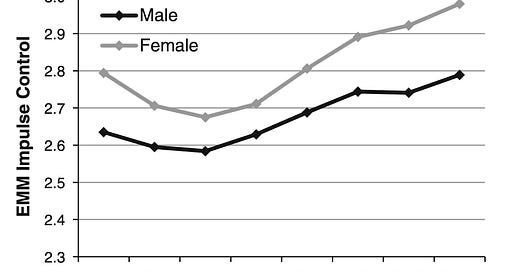

Human development is so designed that puberty starts before the mind is completely mature in its adult capacities for self-control, and hormones undermine rather than enhance the accumulated self-control of late childhood. In educational contexts, I will often show this chart of objectively measured impulse control by age:

Teenagers lose impulse control due to sex hormones and do not fully recover their ten-year-old levels of self-control until 18-19 years old. If your mental model of teenager development is linear, you are going to be sorely disappointed by reality.

Further, I wrote the following in a post relating to the attainment of the middle class:

As I’ve raised teenagers, it’s become more obvious to me the importance of peers. I tell younger parents that their biggest leverage post-puberty is careful control (i.e. range restriction) of their child’s peers. Sex hormones change everything and orient young people towards the future, rather than the past, and they are ultra-sensitive to what attains status among their peers than what their parents think.

Ok, with some background considerations laid down, I’ll attempt to construct a “Half-Baked Unified Theory of Parenting.”

The Window and Cultural Leakage

Humans are fundamentally social animals, and we cannot thrive without community. In a child’s development, this community slowly expands from family to the broader world, and accelerates during puberty, when a normal part of development is a quasi-rejection of the family to find one’s own identity.

This means that the window of early childhood is especially precious for setting family norms. And this experience will be notably different based on birth order. Oldest children will have the longest window of being insulated from outside cultural and peer influences, perhaps until age 12. Younger children will have a shorter window, as peer influences from older teenage siblings will produce more cultural leakage downstream. Thus, the critical “window” for one’s family is the 13 years after the first child's birth.

As I’ll revive as a common theme, you can always loosen up later, but it’s hard to start loose and ratchet down. The job as a parent is to “give ground grudgingly” to modernity, being neither inflexible nor neutral in the face of cultural decline. Like Fabius, pick favorable battles, know when to retreat, and make the cultural enemy’s efforts a net unprofitable enterprise. And in a sense, it’s a battle parents are meant to lose, in that the goal is to produce independent adults who make good decisions, not permanent parental control. We appropriately insulate, delay, mitigate, and arrange circumstances to minimize the influence of modern “mind viruses,” but children, sooner than we expect, will be making their own moral choices.

Thankfully, I’m a “strong opinions, loosely held” type of person, so a Fabian strategy comes somewhat naturally. But for more inflexible personalities, it’s really important not to fall into the Duggar trap of trying to control too much and appearing publicly weird. As I related in my disgust and discretion post linked above:

Reconciling these two principles — the necessity in certain areas to go against the cultural grain and living in community with others — requires the application of discretion. Discretion means keeping one’s mouth shut publicly when appropriate to do so. It means being ok with holding a very different position privately than the rest of society while practicing verbal self-control in public settings when one holds such an opinion. If done competently, this reassures children that having contrary positions on popular foolishness doesn’t mean being a social pariah, and also models how to do the same with their own children, creating a sustainable multigenerational pattern of healthy private behaviors and opinions while still maintaining social ties in an unhealthy society.

After early childhood, peer selection becomes more important. While you cannot control peers directly, you can impose an indirect restriction of range by careful selection of geography, education, and extracurricular activities. This is why people pay so much money to be in the “right” schools and the “right” area. And with so much of the surrounding culture descending into degeneracy, the remaining islands of sanity and function become all the more valuable and expensive.

On Education

As children grow older, they will both need and desire peers their age, and for most people, the educational community they choose will be the predominant source of those peers. Much of this will depend on family resources and local options.

I was once a committed homeschooler, and I still share many of the presuppositions of that world. But like I said, I try to hold my strong opinions loosely. If I look around and notice something askew in my mental model, I reconsider.

I attended a large, competitive suburban high school. I had many smart classmates who attended several reasonably competitive universities, and I experienced real academic competition that motivated me to work harder than I would have without it. It was in this very high school that I met several very talented, ambitious individuals who eventually became critically important partners in my business endeavors.

In the homeschool community, however, I couldn’t help but notice lagging achievement in high school; it seemed like homeschoolers would often start ahead in early childhood but end up behind the “honors” contingent of suburban public high schools by graduation. It struck me as a problem if, whatever the other benefits, my children’s education would be less academically rigorous than mine.

My vision for my children was not of the extreme rat race type — the elite pre-school to miserable childhood of resume padding to “impressive” name brand college halfway across the country to miserable 100 hour weeks at McKinsey to barely afford a studio apartment in a major fertility-shredding urban center pipeline — but it did seem reasonable to provide an opportunity for competitive academics and matriculation, maybe even a scholarship, to a reasonably selective flagship state university or second-tier regional private school, if even only for the indirect benefits.

I do think the university racket is mostly a scam that could be eliminated by employers administering standardized tests to 18-year-olds for entry to on-the-job apprenticeships, but unless everyone coordinates an exit, it’s hard to go against the grain. There’s also the problem that there are barriers to many lucrative, cartel-protected occupations (MD, CPA, RN, etc) that require degrees to sit for the licensing tests, so however practically worthless (or at least inefficient and wasteful) university educations might generally be, it’s necessary to avail oneself of the benefits of these licensing cartels; and in a world of AI and remote outsourcing, a licensed cartel protecting one’s middle class sinecure will become increasingly important. And again, it’s all about those peer relationships, and that continues into early adulthood, and if most of the smart 18-22-year-olds are on college campuses, it’s hard to opt out.

So while we homeschooled early, this “noticing” planted a seed such that a few years later, when we had an opportunity to join a hybrid model school with paid teachers, real grades, real transcripts, etc, but with only two on-campus days a week, we made the switch. I think part of the benefit of this again relates to child development, and it’s a more historic idea than many homeschoolers realize.

The Puritans famously had a tradition of “sending out,” where, around age 13, teenagers would be sent from their homes of origin to another family to serve in some capacity3. Adolescents at this age are often more cooperative and eager to please any adult who isn’t their parent, again because sex hormones activate the necessary psychological process of separating from the home of origin to prepare to establish their own homes, and the concomitant desire to prove and test themselves in the broader world. The Puritans’ elegant solution was to simply “trade” their teenagers with each other to avoid the inevitable conflict.

In an academic setting, teachers and coaches who are not the child’s parents provide this third-party accountability. It is tough as a parent to provide objective accountability while maintaining a loving parent relationship. If one’s child makes a bad grade because they didn’t study, it’s hard to comfort them if the parent gave the grade, and it’s hard for them to learn from the experience if the objective assessment of their needing to work harder also comes from what they reasonably expect to be a source of unconditional love, and when there’s no motivation from competition with other students.

When forced to choose when playing this dual role when homeschooling, most parents reasonably choose love, which results in a better relationship but undermines any accountability for objective results. Functionally, however, this results in coddling. Just as girls often have their fathers wrapped around their fingers, boys are often coddled by their mothers, which is why it’s so important to have third party accountability for some kind of objective result in some part of their lives, to motivate them to suck it up and do hard things so they can eventually provide for a family.

You can almost judge the quality of a peer environment based on the behavior of the boys4, since they are the natural leaders, for better or worse. If the norm for them, especially the popular and athletic ones, is achievement and ambition, it’s a good environment for the girls too5. However, if the boys are underachievers who compensate by denigrating academic effort as effeminate, and are rewarded for whining about school being too hard, then girls will also dial down their efforts so as not to become the objects of scorn, or else hold the boys in contempt. Given the well-documented struggles of young men today, this problem is all too common, and unfortunately, likely only avoided in fairly selective, elite groups.

In addition, much of the homeschooling movement has been influenced by the West Coast hippie “unschooling” contingent, which says requiring students to study things they’re not passionate about is oppressive, so you end up with teenagers with statistically improbable career ambitions related to hobbies. This approach eschews the boring and complicated disciplines that are most consistently rewarded in the economy.

No doubt, there are exceptional parents and self-motivated, agreeable teenagers who make it work. Still, it’s an uphill battle to continue homeschooling into high school, where parents handle assignments, teaching, and grades in increasingly technical subjects, and leaving the cocoon of home is an important developmental milestone. Historically, many teenagers were in apprenticeships or other forms of outside work by these ages, as 14-year-olds were often treated as little adults.

Unfortunately, the most cost-effective solution, public school, remains an unattractive option. It’s not necessarily the ideological problems, which could be overcome, in a generally conservative jurisdiction, by a well-formed faith and worldview at these ages, but again, the peer environment. The biggest problem with public schools6 is that they must admit literally anyone.

Especially with the challenges posed by technology, to be discussed in a follow-up post, it is imperative to choose some sort of school where the community of parents is more on the ball than the general population’s neglect and incompetence. You could almost pose the question as, “What percentage of your teenager’s peers do you desire to have unmonitored access to hardcore pornography on their phones?” Choosing a public school, by default, means an awfully high percentage.

This leaves high-quality, values-aligned7 private schools as the best option for the high school years, but these are not affordable for all families, with tuition from $10,000 to $70,000 per year. Part-time, university-schedule private schools work for more, but again, even half the standard tuition amount is a budget buster for many. There are affordable options for online high schools conducted at home, but “peers” and “teachers” have to be put in scare quotes when those relationships are mediated through a Zoom call and geographic dispersion. The lack of good, affordable options is one of the best arguments for universal school choice, and in the meantime, for benefactors to fund scholarships for otherwise qualified families who cannot afford retail tuition.

On Religion

I made the general case for Christianity and church attendance in my second installment on belief here. I’ll paraphrase again my advice that people who 30% believe in God should 100% go to church. And again, citing the critical development window, between the ages of 2 and 18, a mere 16 years, children will internalize, based on their family’s practices, whether going to church is the sort of thing that’s done or not done. Social science now tells us of the mental health benefits of church attendance, and evolutionary psychology of its adaptive purpose. Since most people for most of history have found value in religion, even agnostic parents should attempt to believe and at least offer their children a chance at faith in a church community.

For Christians in my audience, I’ll offer a contrarian perspective on the intersection of church selection and parenting. There’s an opportunity to connect the critical developmental window with the lost virtues of the past.

My 1980s early childhood is hardly ancient history, when we attended a tiny Southern Baptist church in a rural Louisiana town of 400 people. It was humble, but it had traditional architecture with a steeple and a church bell. Worship exclusively featured songs from the Baptist Hymnal, much as people had worshipped 100 years prior. Our deacons, few to none of whom had a college degree and were electricians, sheriff’s deputies, or construction workers during the week, dutifully wore suits and ties every Sunday, and when offering a prayer, spoke to God in respectful inflections of King James English. The sermons were delivered by our white-haired pastor, whom I thought, as a child, like Moses, got that way through direct communion with God. His sermons were given in the Adrian Rogers type rhetorical high tone of educated Southern gentlemen, undoubtedly picked up indirectly in his seminary studies despite his likely humble roots. There was a sense of dignity and reverence, a residue of the high church Anglicanism that was our common distant heritage before our people spread to the American frontier. Relative to popular culture, Sunday morning was a timeless contrast, not a cheap imitation.

But what I experienced as ennobling, some saw as inauthentic. Today, at many evangelical churches, laity dress in shorts and t-shirts, and clergy can’t be bothered to tuck in their golf polos, else they appear stuffy to the “seekers.” Worship is less a communal act than a concert where volumes are so loud that no one can hear if they’re singing in tune, and forget about sight-reading parts and harmony if you’re unlucky enough to be an alto or baritone for whom the melody is out of range. Emotion in worship is not spontaneous, welling up tears as one hears the tension between the comforting words and triumphal war-march tune of "How Firm a Foundation,” but rather carefully scripted and performative. Much of evangelicalism has degraded to the point where the ultra-liberal National Cathedral features more scripture in a service than many churches will preach in 6 months.

When our children were young, it was still possible to easily find evangelical churches with a traditional format, and we eventually found a home in one of the breakaway Southern conservative Presbyterian denominations, the largest of which is the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Though it happened to also feature traditional worship8, I was initially attracted to this church because of its intellectual culture in engaging with hard questions about my faith in my 20s. In other circumstances, we may have made a different choice, but I was happy, for at least one more generation, to continue the chain with my ancestors in more reverent worship.

As I became acquainted with Presbyterian theology, I observed more benefits. Strangely, these have little to do with Calvinism, of which I am still not entirely convinced, but rather views of baptism and communion. An under-appreciated divide between the churches rests at this fault line. Are children part of the covenant before they are capable of faith? Does communion entail some special presence of Christ of whatever type, or is it purely memorial? Catholics, Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians all answer yes to both questions. Most evangelicals answer no.

These questions orient the foundations of practice either towards a) the corporate body and its worship of God for His glory alone, or b) individual faith experiences, with worship primarily a tool to enhance the latter. The infiltration of California megachurch-style worship and practice into historic, organic faith communities was more successful in those churches already more individually oriented, where traditional practices were running on the fumes of custom rather than enjoying a solid theological footing.

My preferences aside, these are good, faithful churches; they undoubtedly meet “felt needs,” have mass appeal, and teach a saving gospel. In such a context, the culture is almost certainly too far gone to return universally to a more reverent format, which is self-evidently what most people do not want.

Many of these congregations had a tough choice to make in the 00s: a) uphold tradition and continue to bleed families, budgets, and talent to first movers in the market, relegating their church to niche status9, or b) change to give the people what they want. No one is necessarily to blame, it’s just what is. But for individual families, there’s an opportunity, especially when children are young in the critical developmental window, to normalize something more traditional and measured that emphasizes the centrality of God, not man, and teaches important skills like how to sit still and pay attention.

If you have smart kids, an additional benefit is that, among Protestants, conservative churches informed by the Magisterial Reformation tend to have greater intellectual depth. Their theology is almost half a millennium old and continuous with the great thinkers of Catholicism like Augustine and Aquinas, not invented by some self-promoter 150 years ago during America’s 19th-century religious crank-fest. Their members are discouraged from self-interpreting the Bible like a horoscope, but rather rely on consensus documents (confessions, catechisms) informed by centuries of scholarship. Smarter kids are going to naturally have more doubts, and it can be helpful to be a part of a church tradition that can engage intelligently with the best opposing arguments instead of relying primarily on subjective emotional experiences as the basis of faith10.

It’s also essential that children see church commitments reflected at home, most importantly in parents’ (mostly) non-hypocritical behavior, but also in explicit commitments of family time. While I have a friend who has successfully led his large family, toddlers included, through the Bible more than once (and the KJV at that), covering a chapter per day, a more achievable goal I’ve found sufficient is a weekly family Bible study on Sunday nights. Something achievable consistently is better than an ideal avoided. Similarly, one of the more powerful demonstrations of “church is something we do” is to make a point of going to church weekly, even on vacation, even when it’s inconvenient, if at all possible. In parenting, as in most other things, talk is cheap! Action reflects our true core commitments.

Part Two: Practical Applications

In the next post, I’ll take these broad concepts and suggest some practical applications, particularly surrounding the great challenge for today’s parents, managing the strange new world of technology.

Dr. Leonard Sax, a conservative voice among psychologists, makes an interesting case (timestamp 44 minutes) for very limited corporal punishment for boys but not for girls, based on sex differences in psychology. Edward Dutton offers a more comprehensive review of the evidence here. Ironically, parents with low self-control will often be attracted to all-or-nothing approaches as a protective mechanism, which means those most enthusiastic about it are most likely to misuse it. I was surprised to read recently in Paul Johnson’s short history of the Civil War that Jefferson Davis’ father did not use corporal punishment to discipline his sons. Whatever else might be said about that, it demonstrates that avoiding corporal punishment is not exclusively a contemporary idea of hippie parenting.

Right now, I’m involved in a renovation project for what will be, when completed, the oldest operating church building in our city. As I met with the team and discussed various aspects of safety, I said, “remember, teenage boys are functionally [mentally challenged].” We need to assume they will do the dumbest things possible in the building and plan for that, especially in groups, as boys get dumber the more of them are involved in an endeavor. I know, because once upon a time I was one, and I think most adults would have perceived me as one of the more responsible. From 13-16, I did things like, a) throwing a can of air freshener in a fire to see what would happen, and what happened was it exploded like a rocket and hit me in the chest leaving a circular bruise (thankfully I was a good 50 feet away), b) while camping overnight with friends, for some reason deciding it would be funny to attempt to steal a battery off of a bulldozer a mile down the highway from our homes, c) with another friend, who had pilfered a key, entering the friend’s uncle’s apartment to prank call 1-900 numbers in the middle of the night, d) lighting and throwing fireworks at another group of boys across a highway between cars passing as we both hunkered down in ditches, e) almost getting arrested with my friend because I wanted to see how fast my first car would go, requiring my appearance in juvenile court and getting my license suspended for months, f) riding bikes with friends, while parents thought we were asleep, for miles at 2 AM in the morning on tiny country roads for no apparent purpose other than to see where a girl lived. This list continues.

Other colonial cultures handled this differently. Wealthy Virginia boys would often be sent to England to complete an education, whereas girls would be sent to “finishing schools” feminists mock but whose graduates would no doubt outperform today’s college graduates on basic tests of literacy (full fluency in French and mastery of the piano being parts of the curriculum). Poor kids often got no education, of course, but moderately wealthy families would often band together to hire a tutor. The young Robert L. Dabney taught at such a “log cabin” school in Virginia, which would operate maybe three months out of the year when farm labor was less needed, and often finish a full course in Latin on a timeline that would crush most elite high school students today. See, for example, typical 19th-century college entrance exams. The type of modern homeschooling where parents are expected to teach everything is not a historical practice.

The natural difference in maturity levels of boys and girls makes a strong case for red-shirting boys to start kindergarten at age 6, regardless of academic readiness.

There is a debate in Christian circles on the merits of same-sex education. Boys (somewhat reasonably) want to be seen as chill and cool in front of the girls, and thus suppress their competitive instincts in academics when there’s a female audience. The girls can react to this by dialing back their efforts so as not to appear unfeminine. I think the ideal would be sex-segregated classrooms, technically two schools on one campus, but featuring social integration; unfortunately, this type of arrangement is only economically viable in the largest cities.

Another significant problem is governance. Many moons ago, a close, extremely conservative friend of mine managed to get elected to the local school board in an extremely red, 90-95% Trump jurisdiction. And while his fellow members were gut conservatives, they were led around by the nose by the superintendent, a guy with a fake education doctorate who insisted everyone call him “Dr.” So-and-So, and the district’s attorney. This tag team, bolstered by their credentials, was almost uniformly successful in preventing the elected representatives of one of Texas’s most conservative places from doing anything useful. Any residual conservative instincts of school board members were extinguished by their annual “continuing education” at the Texas Association of School Boards’ (TASB) annual convention, where yet more lawyers and fake PhDs dutifully informed them that representing their constituents’ desires was akshually highly improper and “unprofessional” and would likely get them sued by the PhDs’ allies at the ACLU. Their only legitimate role, they discovered, was to rubber-stamp spending increases cooked up by the superintendent and district comptroller.

The superintendent didn’t want any controversy that would endanger his next career move, and the attorney didn’t want to risk a lawsuit that would require actual work to collect his fat retainer. So they excelled at sympathizing with the desires of members to do something conservative while explaining why their hands were tied. And to be fair, their hands were largely tied, to the extent that personnel is policy. “Equal opportunity” according to the Supreme Court turns out to mean that a Christian teacher must live in fear of sharing her faith in one classroom while in an adjacent classroom a man with an exhibitionist paraphilia of some sort is empowered to gratify himself with an audience of minors. “Democracy” likewise means that things 90% of constituents want must be overruled by unelected federal judges with lifetime appointments.

These, too, are rare and must be discerned carefully. Private schools are no panacea, but does the school take action when behavioral norms are violated? Does the school control social contagions by expelling kids who show classmates pornography or act out with public paraphilias?

The PCA’s RUF ministry has done a wonderful job adapting older hymns to updated musical styles and has created something rather unique and distinctive from the bland contemporary Christian sound. It’s also vaguely Appalachian in its use of acoustic instruments, and thus consonant with the PCA’s predominantly Celtic heritage. They’ve managed to keep the high reading comprehension lyrics and lose the soupy, arhythmic Germanic chord progressions.

Complicating this was the simultaneous emergence of the “New Calvinism” movement more efficiently filling the reactionary niche, whose young adherents would find a traditional format, Arminian Baptist church with Finney-esque theology to be weak tea anyway. They wanted to party like it was 1599, singing all 6 verses of “A Mighty Fortress,” rather than sentimental late-1800s hymns like “In the Garden.” Like many institutions, churches were caught in the pincer of polarization. Interestingly, these were not the first “worship wars” in American church history.

An illuminating documentary showcasing the first American revolution in worship is “Awake My Soul,” about the mid-1800s development of shape-note, “sacred harp” singing, featuring deeply Calvinist lyrics reflecting the hardscrabble life of the American frontier, and its subsequent almost extinction by the softer, more emotional “gospel music” movement of the Third Great Awakening.

And to be fair, most evangelical churches are doing a better job with this than they were 20-30 years ago. I remember being surprised a few years ago, visiting a mainstream SBC church out of town that featured a pre-packaged sermon series on the creeds of the Christian faith. As Aaron Renn has noted, a great strength of evangelicalism is its adaptability, though often subject to a significant lag.

I love most of this! My issues are:

1) High fertility, competitive with the Amish, Hutterites, and Hassids, is 7 kids. So any parenting strategy that doesn't facilitate those kinds of numbers will eventually fail over time.

2) I have 4 sons. The oldest is 13. He is a hardworking freshman in college (in the only legit online school that will take thirteen year olds, ASU). He does not watch porn and has ended relationships with friends who attempted to show him porn. He does not play video games and has ended most of his other friendships over this issue. Boys his age only seem to want to hang out and play video games, even the high-achieving boys on his rowing team. If there actually exists this community of hardworking boys who don't watch porn (or play video games) with whom he could compete rather that walk the lonely path he is walking, he would be so happy. And, as hardworking as he is, he would definitely work harder as he is competitive by nature. Despite the additional 6 years of waste-of-time school it would add to his life, I would also be elated for this community. My problem is that I have looked and looked and not found any such community. Moreover, we have attended a dozen churches and have not found a group of boys who don't watch porn or play video games either, let alone boys who work hard.

So I love your post in theory. I am just wondering... have you found this community of hardworking boys who don't watch porn or play video games? Where exactly please?

What about the dual enrollment strategy?

Begin to prepare your child for the ACT and SAT as soon as they're ready.

Enroll in local college as soon as your child can get the minimum required ACT/SAT score.

One or two classes a semester, to start.

Put those classes on their High School Transcript to finish up their high school requirements while they're earning college credits.

Get bachelor's degree at 18.