For most of my adult life, I’ve lived in a midsize metro with a geographically dispersed population in the low-to-mid six figures. Since I grew up in an unincorporated village of 400 people, to me it feels like the big city.

In the entire time I’ve lived here, however, I’ve heard constant grumbling, especially from younger people, about the stultifying nature of living in such a small locale with more limited amenities compared to top-flight suburbs. It’s hard to keep them “on the farm” once they’ve seen Frisco, Round Rock, and Sugar Land.

But historically I have been very comfortable here, as I used to feel a strange sense of alienation from suburban, upper-middle-class people who live in these sorts of places. I considered them “nobodies from nowhere,” mercenary economic units with no organic ties to kith or kin. My family in Louisiana has lived in the same adjacent parishes, a ~10-mile radius, for over 200 years, and it made no sense to me why people would have their extended families spread across the country in the same generic suburbs whether Dallas, Atlanta, or Seattle.

What kind of cold, inhuman person would choose to live in such a way as only to be able to see one’s parents, grandparents, uncles, or aunts by getting on an airplane? Yet, as my horizons expanded beyond my geographically bounded upbringing, it’s become obvious that this mode of living is now the default for most smart white-collar people who, despite most of them not being in a real profession (law, medicine, clergy), consider themselves “professionals.”1

Suburban Secession

My perspective on all of this was challenged a few months ago when I attended a school soccer tournament in The Woodlands, Texas. Prominent throughout the city were banners celebrating the 50th anniversary of their founding in 1974. My city has an urban history going back about 120 years, but The Woodlands, a “soulless” suburb, has a history that is 42% as long; it’s becoming harder to argue that there’s no sense of “place” given a half-century’s history. How did this happen?

The conventional answer is “flight,” that suburbanites fled inner cities due to school integration, expressing with their feet a hatred in their hearts. I’m not so convinced, for more coincident with the flight was not Brown (1954)2 but rather the insane criminal justice “reforms” of the 1970s. A long-lost article I cannot find documented just how crazy things were in that era. The Left had come to full power in the justice system, with their elevation of the criminal and the crazy as not menaces but rather proto-revolutionaries in a genocidal, capitalist system who needed therapy and political cultivation, not punishment. Cop killers would get two or three years in prison, and verbally talented terrorists who assassinated judges or planted bombs were rewarded with college professorships.

Just as Hiroshima was rebuilt from ashes to a gleaming city today, people with work ethic, smarts, and resources can quickly transform a wilderness into a functional urban center, and the cost is small compared to blight and crime. In these new places, resources can be directed to nice things for the community rather than the sinkhole of urban dysfunction. A lot of ink has been spilled reflecting on the cause of the latter3, but the bare fact of its existence is demoralizing for anyone with a dynamic, forward-looking orientation. What if instead of viewing successful suburbs as fake and artificial, they were instead viewed as heroic efforts to preserve a functional way of life amid the cultural destruction of the post-1960s, of peaceful separation to make the best of a bad situation? I’m reminded of Kevin DeYoung’s recent column on how we cannot take on the burden of all of the world’s problems. It’s hard enough to look after one’s own family and their safety and prosperity must come first.

As I’ve matured, I’ve come to appreciate the importance of coordination problems. I have a lot of grand ideas about how society should change, but unless others cooperate with me, being too firm on those ideas personally can result in isolation. There’s an essential truth to “if you can’t beat them, join them.”

A lot of conservatives, particularly those of a contrarian nature, will tend to ignore the default choices of people in moving to suburban areas. It’s much more common to idealize city or agrarian life than the intermediate choice of most smart people with families. Yet when it comes to making decisions for one’s own family, many end up in a ‘burb eventually. Rod Dreher, after moving back to his tiny hometown but before relocating to Europe, moved to a suburb near Baton Rouge. Aaron Renn, who ran a blog called The Urbanist before taking up church and culture issues, now lives in Carmel, Indiana.

Brain Drain

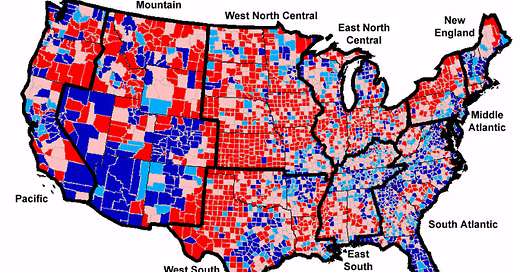

While partially reversed by work-from-home during Covid, the brain drain of more rural areas is a well-documented fact. A study comparing the percentage of the college-educated population from 1970 to 2000 showed that, despite a vast increase in the attainment of bachelor’s degrees (and thus a major cheapening of their value with lowered academic standards), many counties still experienced an absolute decline in their percentage of college-educated population:

Remember this all happened before the hipster gentrification of urban areas in the 2000s; the trend has certainly accelerated since then. The smartest people are moving to a smaller number of urban and suburban areas.

The good news from looking at this chart is that midsize cities seem to be doing fine, as brain drain is most concentrated in rural areas. The mid-tier counties I identified in my piece on Republican voting adjusted for county size are getting smarter, on average. The challenge for these areas may be that those who experience some but limited amenities in a midsize city have their taste cultivated for greater amenities elsewhere. Those who grow up in “counties with significant economic opportunity” and second-tier amenities desire eventually to move up to “counties with a Whole Foods Market.”

Young, single people in particular may wish to maximize their social surface area so good things can happen, whether personal or professional connections for relationships and jobs4. Numbers matter when looking for the best 1:1 fit, and brain drain is particularly salient here as IQ is more correlated in long-term relationships than physical attractiveness. Likewise, the more finite number of job opportunities in smaller cities can artificially constrain the all-important initial conditions for career advancement. This is not to say that moving to a smaller city for the right job opportunity is a bad career move, but rather that limiting one’s search to one particular small city is subject to a lot of random contingencies with timing and availability.

The midsize cities that seem to be doing the best are those with the smallest legacy crime-prone populations and warm but temperate climates, most notably Nashville, which has transitioned from midsize to major in the last two decades, and places like Chattanooga and Asheville. This is particularly salient for women, as high crime more acutely affects their ability to enjoy those amenities that are available.

Given social pathologies spread like diseases, it’s understandable why high-agency people would cluster in enclaves. And as society continues its “prole drift,” more functional neighbors become their own amenity. Obesity by county would show the same pattern from the brain drain chart.

Advantages of Midsize Cities

Other social pathologies, however, are less prevalent in midsize, more blue-collar cities unpopular with hipsters. For those who stay and move to the small semi-suburban outlying areas, there is a refreshing lack of wokeness. To stick around requires a sort of mental toughness, of being able to face the reality of urban dysfunction and accept it without feeling guilty about complex, intractable problems. It’s easier to instill conservative values in children with few preening peers and parents around eager to display the latest narrative foolishness. Strangely, it’s upper-middle-class people who spend the most money to more fully insulate themselves in exclusive enclaves who are most eager to virtue signal silly ideas about it5.

There are other, harder-to-quantify difficulties of the rootless professional. Being away from family necessarily erodes family relationships; there is some discrete number of times each of us will see our parents before they pass, and distance inevitably decreases that number. Likewise, it’s difficult to form those all-important multi-generational relationships between grandparents and grandchildren over FaceTime and occasional cross-country visits.

When parents age and need more intense care, there is no good solution for geographically dispersed families. I heard a story recently of a man who was a legendary high school football coach in Iowa, winning several championships and touching thousands of lives. His daughters had, like so many Midwesterners, located to the warmer climes of Arizona to raise families as upper-middle-class professionals, and their father had followed in old age to be near grandchildren. When he passed away recently, his funeral in Arizona was sparsely attended, whereas in his hometown thousands would have come to honor his life. Cut off from his roots due to his family’s relocation across the country, and forced to choose between friends and family in old age, he was unsung and unremembered in death. An anonymous community based solely on amenities, consumption preferences, and job opportunities doesn’t show up for funerals6.

Smaller cities tend to be more stable communities for the most important aspect of human life, relationships. Most people, including professionals, are locals, and multi-decade adult friendships are possible due to low turnover in the community. Instability in friend groups, for both adults and especially children, is minimized when the default mode of the community is not moving every few years for jobs or promotions for a large employer.

Licensed or highly technical professionals in particular can make serious bank. Especially in cities with a large industrial base but a smaller white-collar population, the demand for attorneys, physicians, wealth managers, and engineers exceeds local supply. Young doctors with stars in their eyes for the big city will prefer a $200,000 salary at a prestigious hospital in a major metro, while their peers willing to move to an underserved locale can print money, earning double or triple that amount, billing Medicare all day for minor surgical procedures in underserved patient populations, all with a ten-minute commute for an early afternoon tee time. A local wealth manager told me he enjoys much lower and sleepier competition in our city and as a result, using big-city marketing techniques has grown his AUM to one of the highest in the country for someone his age. Engineers who stick around for local refinery work, instead of angling for a cubicle job at corporate headquarters, earn the same as their peers in the city but their money goes a lot further7.

This is particularly true in the most significant purchase for most people, a home. A friend of mine in central Scottsdale enjoys monitoring my local Zillow listings and says that, in Texas, and particularly our city, “houses are basically free.” He lives in a sub-1500 SF three-bedroom ranch house rental that, if sold, would go for about $750,000 as a tear-down. His house is worth more dead than alive. Meanwhile, less than that will get you a newly constructed palace with a Viking range and an acre of land 15 minutes from the city center in an adjacent exurban county:

The likely buyer, if local patterns persist, will eventually add a large metal building in the back of the oversized lot to hold various toys — a man-cave with a retro-themed bar, pool table, and large TV, golf carts, ATVs, maybe an unnecessary tractor — from the bounty of his low-cost lifestyle. Crime is almost non-existent among a highly armed populace, easily 10+ firearms per capita (not kidding), eager to make use of castle doctrine if given the opportunity, and friendly local prosecutors who won’t ask many questions about self-defense against a lowlife dumb enough to break into a home in a 90%+ Republican jurisdiction. His children will roam the local streets unsupervised in the golf cart, exploring ditches and ravines to catch snakes and other critters, and twice a year hundreds of dollars will be lit on fire in total freedom to conduct personal fireworks shows.

It does, however, take a particular personality to enjoy this fully. Some would say white collars cover red necks, if someone wanted to be derogatory about it. A better description comes from Paul Fussell from his seminal book Class, in that the area is psychologically, regardless of actual occupation, “high prole.” These are people who are liberated from the mental weakness of status-seeking, insecure middle-class strivers and are more similar to true aristocrats of the old type. He explains that,

“…. their disdain for the middle class is like the aristocrat’s from the other direction… and ‘have gone to the top of their social world and need not expend time or energy on social climbing.’ They are aristocratic in other ways, like their devotion to gambling and their fondness for deer hunting. Indeed, the antlers with which they decorate their interiors give their dwellings in that respect a resemblance to the lodges of the Scottish peerage. The high prole resembles the aristocrat too… in ‘his propensity to make out of games and the sports the central occupation of is life…’”

Let’s compare to a comparably priced home in Austin, the most expensive market in Texas:

Built in 1956, a classic! Though probably best not to own a gun unless you can arrange for a gubernatorial pardon.

Contrarianism is a tricky business. Clearly, there are advantages to major metro areas given the higher cost of living. Usually, market prices exist for a reason, and betting against them is dangerous. Austin has about an extra month of decent weather, and mornings and evenings are tolerable year-round due to low humidity. That said, I’m fairly confident that those lucky enough to have good job opportunities in lower-cost areas enjoy a huge net benefit, but often it takes a lived experience to figure that out. It’s extremely common for young people from our city to move away in frustration of what they think they’re missing, then move back once they have families and miss the tight-knit community and glorious lack of significant traffic.

A huge explanatory factor here is the perceived value of certain amenities versus their actual value. Few people actually desire or can afford to shop at Whole Foods exclusively, and Kroger or HEB carry all of the organic foods that matter, without requiring a separate trip to avoid hippie household necessaries like shampoos and detergents that don’t work at a ridiculous markup. I’m not sure outdoor amenities are utilized all that frequently, as most of us are blind when we get caught up in the busyness of our lives, especially in workaholic big cities, to local activities, especially post-children8. A Peloton and weights in an air-conditioned room, enabling low-injury-risk physical efforts at the border of capability and failure, are more critical to fitness improvement than a few local hills and ravines worth hiking. Lower cost of living and a slower, less rat-racey pace of life also enable more frequent vacations with blocked time to enjoy amenities in other places.

The Texas Solution

In writing about this, I realize my hypocrisy. I no longer live in the tiny community I grew up in, and sought out a larger metro for my adult life rather than where I was raised, though I did stay within driving distance. I’m reminded of the old 80s drug commercial when advocating for localism: “I learned it from watching you!”

When I was a preschooler, my parents bought 5 acres of land and built a modest home. They intended to create a “homeplace,” a common arrangement in the previous generation (and still not uncommon among my extended family), where their children could have a place to build their homes on adjacent land. Life had other plans for us. We lived there for about ten years before relocating to a subdivision in a larger, more suburban school district with better academic opportunities. And as much as I would love to visit my adult children and future grandchildren on a golf cart, it’s an even less realistic dream today. It’s overly romantic to expect the old sort of multi-century organic roots in an economy whose prosperity grows by increased specialization.

Ironically, Texas, in aggressively growing metro suburbs across several economic powerhouse regions across the state, enables a very achievable driving distance proximity. It’s possible here, and common given the critical mass of the state’s economy, for extended families to be no more than 3-4 hours apart with no compromise on economic opportunities. On net, in its emphasis on jobs in highly technical sectors, Texas seems to be getting smarter, if comparable standardized test scores are analyzed.

Perhaps the achievable ideal for professional extended families is frequent, doable road trips, between equally nice suburbs in DFW, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin. Demographers call this economically dense super-region the “Texas Triangle,” and right at its beating heart, nearest its population-weighted center, sits College Station.

It’s a compromise that certainly beats the hell out of cross-country Thanksgiving flights.

As I covered in my review of BS Jobs, many, but not all, of these occupations represent sinecures feeding on some long-dead-or-departed entrepreneur’s business and brand equity. The work may be intense but is largely CYA paper shuffling and layered consensus-based responsibility sharing for non-owners who are called to make major operational decisions and naturally want to avoid getting fired. Politics, not merit, often determines who gets hired or promoted, and the management class is geographically concentrated; they like nice things. Especially for two-income households, a larger metro area is often a necessity to provide an adequate job market for two. Absentee, passive capital, especially when anesthetized to cash returns by the capital gains casino, accepts a lower rate of return on the actual business for not being bothered or stressed, and management vacuums up the vig they can get away with; I do not judge, for this is the way of the world, and “owners” who don’t participate materially and invest passively tend, in the long run, to get a cash return commiserate to what they contribute to the economy. The Kafkaesque pointlessness of many of these jobs, however, is demoralizing, with many highly successful corporate drones, despite the largesse of inflated management salaries, fantasizing of a Shark Tank-inspired escape to entrepreneurship. Man does not live by bread alone.

The integration process was not as straightforward as history books portray. Outside of a few places in the very Deep South, integration, at first, proceeded reasonably peacefully; “separate but equal” schools were eliminated. Social engineers of the Left, however, were dissatisfied with the resulting demography of integrated neighborhood schools. Radical federal judges, starting in the 1970s, proceeded to gerrymander district lines, and bussed children across cities to achieve desired metrics. As late as the 1980s, I had cousins in Baton Rouge who were bussed 45 minutes one-way due to a single federal judge overriding the decisions of their elected representatives. Poorer children, of all races, bore the cost, as wealthier people could escape by moving outside the jurisdiction, usually to an adjoining district outside the reach of the judge’s order. Often these court orders were sources for grift. My high school is still under a half-century-old federal order, and a few years ago the NAACP, a party to the original litigation in the 70s, demanded money from the school board to establish certain “magnet schools,” to transfer tax money from the suburban part of the district to their preferred jurisdictions. The school board refused their extortion, so they filed a new complaint under the order to redraw district lines that had been in place for 30 years, among other demands, and communities that had been part of certain schools for decades were arbitrarily threatened with displacement for their elected representatives’ refusal to transfer their property taxes across the district. The Left’s complaints about the reversal of the Chevron doctrine leading to a dictatorial judiciary rings hollow; they are perfectly fine with judges micro-managing the smallest levels of government when pursuing their objectives.

John Derbyshire discussed the political impossibility of the situation in a Chronicles column a few years ago. He advocates for a culture-first approach, which is good politics but unlikely to improve inequality. Culture is highly intransigent from a top-down policy perspective (20th-century totalitarian regimes tried and largely failed) and can only be reliably changed by supernatural means, and we have no control over the movements of Providence. We can certainly advocate for the removal of political programs that incentivize fatherlessness and the resulting crime, but again we have little individual control over politics. In the meantime, we are called to do what is best for our families.

Sex ratios, strangely, seem to have a geographic vector to them. Large Eastern cities are the worst for women, especially New York. I once had a conversation with a pastor associated with Tim Keller’s church. He said the biggest challenge he had with the churchgoing men there was that there were so many beautiful, educated, available women it was almost impossible to get his guys to settle down and commit. Was Sex and the City that powerful as a cultural meme?

Even in ostensibly conservative places like The Woodlands (the largest city in the top outlier, Montgomery County, in my list of large Republican counties), a city built by hydrocarbons, parents struggle with upper-middle-class self-loathing and posturing among their children. A recent Wired article profiled a startup there seeking to use fracking technology to make geothermal energy cost-effective in more varied geographies. The oil and gas engineers who took a pay cut to work there related, “Their children, they said, were finally proud of them, proud of their work. Lance’s kids joked that they could, for the first time, tell people what their father did for a living.” Ungrateful brats biting the hand that feeds them! Imagine raising your kids in a conservative place built by oil, then watching them be brainwashed by midwit science teachers into being embarrassed by you for working in an industry that has done more for human prosperity (and Christianity) than any other.

The increase in the popularity of cremation also speaks to the nihilism of urban professional life. Instead of being laid to rest with ancestors, to “sleep with their fathers” previously passed in the same location over the centuries, people have their ashes scattered momentarily over some remote outdoor location of personal significance.

And, I would imagine, are happier being closer to the physical fruits of their intellectual labor. Marx, an egghead, misunderstood the satisfaction most people get from manufacturing work. The most alienating work for most is that which is most abstract.

A key component of my partners and I’s lifestyle design strategy is to build out amenities for ourselves and our team that are extremely local, minimizing the critical friction in actually utilizing them regularly. Even a 10-minute drive is often behaviorally prohibitive, e.g. the proven business model of gym memberships in betting successfully that most members will rarely show up. Distance and time seem to scale exponentially in inhibiting frequency. I think this follows for family relationships as well.

Interesting read. We are ex-pats and constantly flirting with the idea of moving back to the USA, but as we are both from mid-Atlantic suburbs, going back to those areas is not terribly attractive. We figure that all mid-sized cities will offer the things we are looking for, so narrowing down the choices has so far been impossible.

Someday when this degree is over (idiot young me had to go to school 2 thousand miles from home) I will return to South Wisconsin and enjoy a life of road maintenance, deer and pheasant hunting, and college football. Alas paradise is a few years out still.