In this final post on my reasons for belief, I’ll deal with the objection that has caused the most personal struggle: the doctrine of hell, which has taken me more time to write. It begins by assuming the Christian faith is true, building on the case for theism (Part One) and the case for Christianity specifically (Part Two), while Part Three dealt with other common objections I find less personally problematic.

In my early 20s I went through a pretty serious crisis of faith. I, like many Christians, had come to a point where I could not imagine a just, good God wanting to torture his enemies for all eternity. If I, as a fallen, corrupt human being, would not want to do that to my own worst enemies, how much less could such a thing be expected as part of the character of a pure and holy God? Many seeker-sensitive churches soft-pedal on this count, but the issue is unavoidable; Christ discusses hell continually in the gospels.

We all instinctively cringe at fundamentalist sects who seem to rejoice in the future suffering of unbelievers, yet this rejoicing is exactly the emotional leverage used by Jonathan Edwards in his famous sermon, “Sinners In the Hands of An Angry God.” Edwards asks the listener to imagine their mother, or children, or other loved ones praising God and thanking Him for His righteousness and justice for the listener’s burning in hell forever.

Edwards’ motivation is evangelical, of course, not judgmental legalism, but the emotions he describes are so hard for us to conceive they might as well be imaginary. If it is inconsistent with Christian character today to rejoice over those in hell, how can it be part of our rejoicing when we are glorified and perfected? It may be possible, but such a huge gap in affections between our current state and that future state is such that we cannot identify with it and integrate it as a salve for doubts.

Theories of Justice

It may come as a surprise to some readers, given my conservative convictions, that I’m a big softie when it comes to thinking about eternal punishment. However, there are huge differences in what works in a fallen world with limited law enforcement resources and a largely unchangeable human nature, versus eternity with a benevolent deity with unlimited knowledge and power. Down here, I’m a realist with an economist’s acceptance of inevitable tradeoffs.

Among human theories of justice, I find two most compelling: utilitarian and deterrence. Criminality, in my view, often involves an extremely high time preference that is not always cold-blooded malevolence. Maybe they have an extremely low IQ, or bad genes, or a horrible upbringing, and sometimes all three. This is consistent with liberal thought, but my instinct given this is not to avoid any kind of punishment but rather to prioritize the needs of the functional over the dysfunctional.

On a utilitarian basis, removing criminals from society protects the functional from their potential future crimes. And given we catch many fewer crimes than are committed, and the high likelihood of repeated behavior, separating the criminal for an extended period protects the functional members of society1.

Deterrence is a further purpose of punishment of criminals. There are people with moderate levels of self-control who will be motivated to avoid crime if crime is punished.

For some acts, especially murder, those causing permanent disabilities, or sex crimes, there is a further purpose of retribution. These are crimes where a victim and/or their family are permanently wounded beyond the psychological capacity to fully recover in this life. Capital punishment in particular can give a therapeutic closure for victims, by showing that the surrounding society stands with them and that while they may be wounded, the perpetrator no longer walks and breathes among us. The deterrence and utilitarian aspects of course follow, in that an executed criminal serves as an example and can no longer commit crimes in the future.

The Left, at least for those criminals among their client classes (MAGA grandmas excluded, at whom the book must be thrown), often supports what they call “restorative justice.” Their idea, at least in its honest form that does not portray the criminal as a victim, is that modern psychological and sociological methods are sufficient to restore the criminal mind to sanity such that it can eventually reintegrate into society.

I’ll grant that for somewhat “victimless” crimes like those involving substance abuse, alternatives like drug courts that focus on strict accountability in view of restoration are often better than traditional models of punishment-based justice. For the truly criminal who harm others, however, psychological and forensic science agree with Christian theology that man is largely imperfectable. Psychotic, abusive, and violent behavior is most resistant to therapeutic intervention.

In an eternal view, however, restorative justice is possible. An omnipotent God is undoubtedly able to both heal the victim’s wounds and ameliorate the perpetrator’s deformation of the soul. That the Christian God does not elect to do so begs the question of why. If a charity traveled to an infection-plagued backwater with 1,000 doses of life-saving antibiotics and chose to only distribute 200 of them and trash the rest, it would be natural to blame them for cruelty in having the means to save but choosing not to do so.

Now this is an imperfect analogy, and it might be objected that perhaps only 200 wanted the medicine, and the remainder irrationally rejected it. God, however, can cause people to believe or take whatever action He desires. So why does He not, if this is in their best interest?

Coercive Evangelism

This doctrine is also a huge evangelical hurdle. No one likes being coerced, and smart unbelievers will object to a message that says, essentially, “Believe me or burn in hell forever.” That so much of the evangelism of the 20th century was of the turn-or-burn variety gave many unbelievers a very low view of Christianity as a belief system for the weak-minded and easily manipulated.

It’s also bad theology, in that it presupposes that faith out of fear can precede regeneration, but that’s a different topic. I also can’t help but notice that this narrow evangelical focus is also manipulative of believers, in coercing fundraising for missions bureaucracies and justifying utilitarian approaches to church practice2.

No Good Answers

My response to my faith crisis was not to abandon the church, but rather to deepen my search for answers, while still attending church and believing the best I could. A turning point for me was reading Lee Strobel’s The Case for Faith (the follow-up book to The Case for Christ). It’s not a particularly scholarly book but provides an easy overview of the best apologetics for these types of questions.

As Strobel interviewed the very best and most thoughtful conservative theologians of our time, I realized for the first time that no one had any good answers. As I continued to have conversations, often privately, with other thoughtful conservative Christians, I realized many struggle with this issue and likewise lack any satisfying answers, but I think people keep quiet about it lest they be seen as lacking fidelity. It’s a fair concern.

Since so many people who begin to question certain doctrines are often seeking to justify literal infidelity of some kind — or more common in our low-testosterone age, a Christian psychologically broken by regime pop culture propaganda who can’t handle the Bible’s endorsement of natural law, and the almost universal testimony of mankind until 50 years ago, concerning biologically dysfunctional paraphilias — I do feel it’s fair to ask where someone plans to land the plane in the moral realm.

Whatever doubts I have from time to time, I have never ceased to believe that traditionally understood Biblical morality is simply a clearer view of natural law morality universal in the human conscience, and pagan and Christian societies used to agree, at least directionally, on these things, and I’ve never questioned that moral law, though of course, I struggle like everyone to fulfill it, and I never considered leaving the church.

Embracing Mystery

And so, in an almost Roman Catholic fashion, I shifted the basis of my faith from absolute belief in all of the apparent claims of the Bible to a loyalty to the Church itself. I assent to the Bible’s claims where I struggle to believe, but my faith is in Christ alone, not my degree of belief. If the theologians Strobel interviewed could live with not having good answers to why a just God would condemn people to hell forever, and remain Christians and part of the church, then I could as well. It was a key moment in my spiritual maturity as I accepted a doctrine of mystery for the first time.

As I mentioned in previous posts, non-churchgoers seem to think Christians are always 100% certain in our beliefs, as if that’s a price of admission. I saw a great take on Twitter that said “People who 30% believe in God should 100% go to church.”

My doubt is never quite that extreme, but my belief can dip to the 70% level from time to time, and this is perfectly normal, because, again, it’s called faith for a reason. Strangely, my doubts tend to center not so much on newly found rational arguments, but rather they find rationalizations based on my moods. When I’m a little down, I doubt more, and when I feel good, I doubt less. Increasing my exercise efforts, getting better sleep, and otherwise managing my neurotransmitters is usually more productive than overthinking these doubts.

Nevertheless, many continue to struggle with the doctrine of eternal hell, and as I’ve wrestled with it for many years, similar doubts have been voiced by people very close to me who want more solid answers. Their questions have challenged me to describe my best answers for this difficult doctrine more adequately. Having these answers close at hand can at least provide a spiritual handrail of sorts when doubts creep up.

I group the possible solutions to the hell problem into five general groups, in ascending order of theological “creativity:”

Option #1: Our Sense of Justice Is Flawed

Have you ever had the experience of dreaming and having some firm conviction about a person or idea? Yet, upon waking up, you realize the conviction was delusional, and you are instantly returned to your normal ways of thinking. Perhaps, at the moment of our glorification, the scales fall away from the eyes of our moral conscience and we will understand the justice of the Biblical doctrine of hell as classically understood.

This does little to illuminate the issue but merely confirms the mystery. But, the fact we can experience delusions in dreams, and then be instantly cleansed of them upon waking, shows we are capable of sudden changes to our moral perceptions. This provides a logical basis for why the mystery of the doctrine of hell is opaque to us now but may be clear later.

A logical weakness of this option is that it stands opposite to our usual sense of fallen justice. If anything, fallen man is too bent on revenge and punishment when he has been wronged. The Old Testament law’s provision of “cities of refuge” is an example of this - God knew that sometimes man’s sense of justice was more severe than His perfect justice. Yet, how is it, in the most severe and permanent possible punishment, some of us become relative humanitarians?

Perhaps it is that we are looking for a license to sin. Our remaining sin, while pleasurable, also triggers our fear of judgment. We hope for leniency so we may have our sin cake and enjoy heaven too. The danger of a desire for the license to sin to cloud our judgment is significant. If we escape its influence for a moment, we can see how it might distort our thinking of God’s justice. What purports to be compassion for all could simply be compassion for the sinful self.

Option #2: Hell’s Punishments Are More Proportionate Than Some Assume

I call this the Dante option. In The Inferno, Dante describes certain levels of hell as more tolerable than others. He imagines the virtuous pagans, like Virgil, inhabiting a first circle of hell that is not the paradise of heaven but comparably hospitable to Earth. If it had the Mediterranean climate of Italy, it might be more enjoyable than much of Texas.

The idea of different severities of punishment in hell is certainly implied in several places in the Bible. It could be that general descriptions of hell are largely correct, as a place of eternal pain and torment, but within this, there are exceptions or modifications based on what God’s justice would require. The Old Testament law certainly distinguishes the severity of punishments based on the severity of the sin.

Under this idea of hell, those who reject God’s grace and use their liberty to sin as a license to hurt others will be more severely judged than those unbelievers who otherwise live virtuously. We speak here of course in relative terms, as men compare each other. Man, apart from grace, receives the just punishment for his sin. That these just punishments might be vastly different is no mark on God’s justice, but rather a credit to it. Perhaps in our understanding of hell, and in a mistaken zeal to enhance evangelism efforts, we have taken poetic language about the “lake of fire” or summary statements about the nature of hell to be exhaustive and literal.

The Christian receives grace from punishment, but more importantly, access to God Himself in the new heavens and the new earth. The “gnashing of teeth” could be less about pain in some cases and more about regret, particularly if a person knew the truth yet suppressed it.

I read a solid theological argument a few months ago, in a Reddit post (originally here) by a self-identified PCA elder that seems to have disappeared, along these lines that relates the doctrine of hell to the wide latitude given to judges in ancient Middle Eastern culture:

Yet that is what many think hell is like—utter and equal torment for unbelievers for an eternity. But I don’t think the Bible teaches that.

…

So first, by understanding that the afterlife is described in figurative language, we can see that people are not necessarily rolling around in lava for an eternity, no more than Christians are laying in Abraham’s lap forever. That means hell is very frightening and no one should want to go there, but the lake of fire is symbolic of an inescapable uniform judgment, like a swimmer dropped off suddenly in the middle of a stormy sea, with no boat and no hope of the storm letting up.

The second matter that’s important to seeing God as a righteous judge is reading Jesus’ words about hell and its great fiery torments in context of the Old Testament law and system of judgment.

…

Jesus, when describing the great punishments of hell, was, just as the rest of the Old Testament and other legal systems of Moses’ day, described hell at its worst, in terms of its maximum possible punishments. He did so as a warning and so that he, as the judge of mankind (See Matthew 25), might exercise justice and give proper punishment that fit the crimes of sinners who reject him, just as the Jewish judges God established of the Old Testament and New Testament times did.

In Old Testament times, there were other legal systems around like the Law of Moses. You’ve heard of the Code of Hammurabi, and the Egyptians also had an extensive legal code.

They all did the same thing as the Law of Moses--they gave punishments in terms of their maximums. Judges and elders were then called upon to adjudicate the proper punishment that fit the circumstances and motives, but were bound to not go beyond the maximums stated by the king.

Exodus 21:23-25 makes it plain that judges and wise elders of the city would oversee sentencing (Exodus 18; 2nd Chronicles 19). And so the book of Proverbs now makes sense as it says dozens of times for rulers to learn to show mercy—why? Because mercy is what was exercised every time they made a legal ruling, since the punishments were all stated in terms of the maximum penalty possible.

Moving ahead to the gospels, when Jesus describes hell and its punishments (Matthew 13, 25; Mark 9), wouldn’t Jesus have described the harsh reality of the afterlife in terms of its maximum penalties, just as the OT does? With the obligation laid upon himself (Matthew 25) to properly sentence humanity after the resurrection?

Paul seems to assume that in Romans 2:5:

But because of your hard and impenitent heart you are storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath when God's righteous judgment will be revealed.

That is, by your continued sinning, and your pride, and lack of repentance, you are making your judgment worse, and you’ll see that for certain when Jesus returns to judge righteously.

…

With that in view, now I can see myself in heaven, and looking down into hell, I can see those who deserve to be there and I’ll feel even better than I do today when I see people in a prison—without concern about injustice, I'll be glad they were caught and stopped from harming themselves and others. The fact that those in hell will never be free means they will never be free to sin against God’s people, never be free to hurt anyone but themselves. That sort of incarceration doesn’t make God look bad nor does it torment me emotionally, as they are punished in a way completely suitable for their crimes.

In other words, ancient judges in these cultures were not automatons issuing mechanical statutory penalties; they had significant latitude to show mercy. God Himself does much the same in not applying the maximum penalty to any number of capital criminals including Cain, David, the woman caught in adultery, and the Apostle Paul. That such a cultural pattern might be embedded in Christ’s warnings about hell is entirely plausible.

Option #3: Hell Is a Choice

C.S. Lewis provides us with a third option in his classic The Great Divorce. He shows us a model of hell where the denizens are allowed to leave, but are so impoverished of soul that they would rather stay in it, slowly fading away and being consumed in their selfishness but never completely disappearing. Absent God’s common grace, people eventually lose all desire to be reconciled to Him. I find Lewis’ vision to be inadequate, as it borders on a doctrine of annihilation, but it remains a possibility.

A greater choice could be implied from a passage in the third chapter of the first epistle of St. Peter:

18 For Christ also hath once suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh, but quickened by the Spirit:

19 By which also he went and preached unto the spirits in prison;

20 Which sometime were disobedient, when once the longsuffering of God waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was a preparing, wherein few, that is, eight souls were saved by water.

Note that the immediate context refers to the damned of Noah’s flood, not solely Old Testament saints as sometimes assumed.

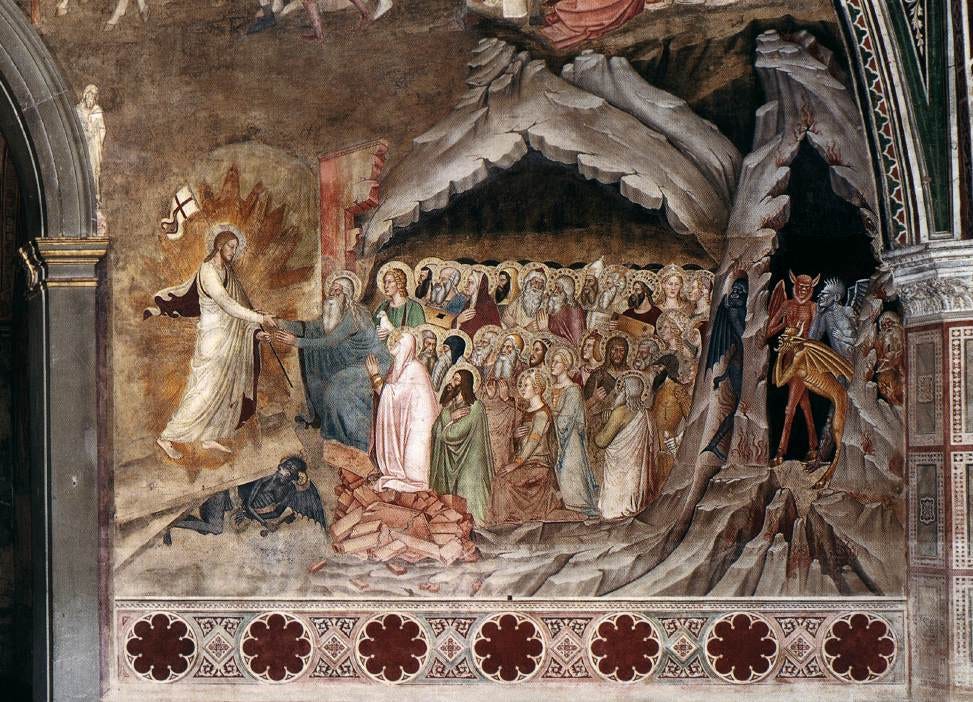

The Apostle’s Creed also states that Christ “descended into hell.” Reformed folks often want to hand-wave these types of passages away because they complicate their hermetic soteriology. Yet the oldest traditions seem to take them more literally, as depicted in this fresco (circa 1366) in the Spanish Chapel at the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence:

Depicted here is Christ breaking down the doors of hell, crushing a demon under His feet, and then ministering to the souls inside. If this population had a second chance after death, or more precisely an opportunity to make their election fully manifest, it is plausible all have such a choice. Nor would this be a choice all would necessarily make, given that salvation requires a fundamental change in nature and submission to authority that many would no doubt reject.

Nor would it compromise God’s holiness for this choice to be given without the veil of this world, and nor would such a choice in the face of full revelation be necessarily coercive. After all, the angels, in the heavenly civil war, made diverse choices with all of the relevant information, no fundamental sin nature, and none of the cloudiness of limited human perception of the divine. Most importantly, those provided with such a choice and undeniable evidence of its consequences certainly could not call God unjust for their continued and chosen rebellion.

Option #4: Hell Still Leaves People Better Off Than the Alternative

A basic principle of common law litigation is you can’t just sue someone because they did something you didn’t like. You must show specifically how you were damaged by the defendant’s actions.

Seen in this light, Christ’s “Parable of the Laborers” (Matthew 20:1-16) might be the most politically incorrect passage in Scripture. It is a full endorsement of the fundamental justice of inequalities in opportunity and outcome as long as the specific promises to each individual are kept. The landowner has a complete right to contract for wages unequally, and laborers have no right to complain when the landowner blesses someone else, even if they are denied the same opportunity.

So what does this have to do with hell? One of the most potent criticisms of the doctrine is that God would be more just if He simply annihilated the souls of the damned instead of subjecting them to endless torment. Alternatively, God could have chosen to never create any non-elect people who would be sent to hell. However, what if annihilation or non-existence is worse? What if not existing at all is worse than existing in hell?

We all have a very strong instinct of self-preservation and feel strongly in our souls that our chief desire of existence, unless we are suicidal, is to continue existing. People hate aging not only because of what it does to the body, but also for what it foretells.

Many respected theologians believe that a sovereign, holy God could not but build the best of all possible worlds, at least as an end state. This means that the outcome of eternity, including those in hell, will somehow be better than if Adam had never sinned. God uses sin to achieve His purposes without participating in it. This may be true, and I believe it is true, that God is working towards the best possible end of history, however meandering the imperfections along the way.

We don’t have to go that far, however, to defend God’s justice, if it were true that existing in hell is better than not existing. God’s options are to a) not send anyone to hell, b) not create people who would be sent to hell, c) annihilate those who would be sent to hell, or d) send some people to hell. If existing is always better than not existing, no one can complain of injustice who is better off than if they had never existed or been annihilated. That God chooses to save some still leaves the damned soul better off than any other alternative besides universal salvation.

Of the more severe punishments we imagine in hell, it is hard for us to conceptualize how existing there would be better than not existing. Yet, if the basics of human psychology remain, the punishment would at least seem less severe over time. Our minds quickly find an equilibrium to nearly any situation, good or bad - psychologists call this “hedonic adjustment” and it is one of the few experimentally repeatable laws of psychology3. It’s up there with IQ testing and exposure therapy in terms of empirical robustness.

The rich man is not happier than the poor man, he just has a different set of worries. Surveys show quadriplegics are about as happy as those without a severe disability, and people who become disabled through some accident, after an initial period of depression, end up as happy as they were before. And despite the negative hype of the news media, surveys show most human beings worldwide are happy, even in this world of pain and death. We enjoy existing to about the same extent regardless of our circumstances.

Is our desire to exist stronger than our desire to avoid pain? If so, it could be that the residents of hell still prefer existing in that state to not existing at all, in which case they are better off and cannot complain about their eternal state, even if some receive unmerited grace.

Option #5: Grace Is More Extraordinary Than We Imagine

The classical Christian doctrine is that only those with faith in Christ partake in the salvation provided by His sacrifice. Yet this is an oversimplification. Nearly all Christians believe that people who are incapable of faith, yet die, will be saved apart from faith. Infants and children, for example, about half of whom died before capable of faith for most of human history, are saved without faith4.

Nearly all believe that adults with developmental disabilities that would prevent the apprehension of faith are likewise saved without faith. They are saved by Christ, but not because of their faith. Hence, some are elected to eternal life without faith, perhaps even a majority of the total elect given historical child mortality statistics. According to the Westminster Confession, faith is the “ordinary” means of salvation, but this does not exclude or limit God’s complete discretion in the use of extraordinary means. “Extraordinary” does not necessarily imply a smaller number.

If we admit this category of salvation without faith, it is hard to draw a precise line as to what constitutes enough of an inability to believe to qualify under extraordinary grace. It is quite clear that the human mind and spirit are constrained by all sorts of physical limitations and traumas that might affect the ability to have faith or show the marks of faith.

The famous case of Phineas Gage illustrates the point. Gage, a highly moral, respectable person, gets a spike driven through his brain in a workplace accident and survives. Afterward, he loses all self-control and turns into an evil, hateful person. Obviously, the cause of his immorality is the damage done by the spike to his brain. Gage would have been physically incapable of showing the ordinary fruits of faith after this accident5. A Calvinist unaware of his condition might say he could have no assurance at all, as willful engagement in serious repeated sin does not evidence saving faith, which always perseveres6.

Similarly, Parkinson’s patients on L-Dopa, which stimulates the brain’s reward systems (which overlap biochemically with its movement system), often become severe sex, gambling, and drug addicts despite living a moral life before the medication. The effects of our body and physical limitations on our ability to show the marks of faith, or even to have faith, are undeniable. We know now that early childhood trauma has indelible and permanent negative effects on brain structure.

If we were to say that the 60 IQ victim of severe fetal alcohol syndrome requires no faith to be saved, how can we not admit the possibility that the survivor of childhood sexual abuse might be similarly handicapped in their ability to trust the unseen God? What about the soldier with severe PTSD who commits suicide?

Even ordinary salvation might be broader than some assume. Christians have often wondered about the prospects for the God-seeker far from any hope of hearing the Church’s gospel message. Though rarer today, strictly speaking, in our hyper-connected world, there are barriers other than geographical that might affect the realistic odds of someone being responsive with the ordinary marks of faith, whether a Muslim child raised in Saudi Arabia, or an American raised in a godless family and catechized by the materialist claims of the so-called scientific consensus.

We simply don’t know what “seek and ye shall find” looks like in different contexts. The first and second chapter of St. Paul’s epistle to the Romans seems to contrast between regenerate elect and non-elect pagans and how their faith or lack thereof manifests in moral behavior absent revelation, though Paul’s particular outcome-based taxonomy concerning sins against nature would be offensive to many today.

The “line” so to speak where a person, in their particular situation, is accountable for confessing faith to be saved is ambiguous with a moment’s reflection on our part. We will never know where this line is, of course, and I believe this is on purpose. God could never tell us7.

Of all theological truths, the most self-evident is man’s depravity. Carnal man desires more than anything else a license to sin without consequence. If God were to publish that an 80 IQ was the absolute minimum necessary to be accountable, men would be lining up to have parts of their brains taken out, or deliberately do poorly on IQ tests, to show they had an absolute license to sin.

Whatever extraordinary conditions God were to delineate as exempt from the requirements of faith, and the fruits of obedience, men would eagerly deceive themselves that they fell into this or that category to preserve their precious sin. As a result, sin, death, hate, oppression, cruelty, and destruction would multiply exponentially.

In other words, any revelation of God’s secret will to be more merciful in his dispensing of grace would create hell, right now, on Earth, for everyone, in man’s current depraved state8. The revelation of Scripture is precisely tuned to minimize sin, maximize goodness on this Earth, and make plain the path of salvation most beneficial in this world and the next.

Could All Be Reconciled?

In the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, it is permissible to pray for, but not expect, the eventual salvation and reconciliation of all. This is not cheap, hippie universalism, but the idea of a possible reconciliation after a fixed term of punishment in hell.

Yet while I will not deny the possibility outright, it is very clear that any such idea must be handled very carefully. Man is so depraved, so extreme in his preference for pleasure now, damn the consequences, that even, say, a one-million-year sentence for a minor sin would serve as a license to that sin. Only the idea of an infinite punishment of infinite duration can adequately offset, and then only imperfectly, man’s degenerate, high-time-preference desires.

I have a couple of friends who are or have been prosecutors for the state. In my conversations with them, I have learned that if the general public knew how easy crime was to commit, how infrequently it is caught and punished, how severely low the resources the state has to prosecute it, and the relatively light sentences given for many serious crimes, many more people would be lawbreakers. Our ordered society would quickly descend into chaos, and it is only the veneer of justice that keeps people even partially in line. The fear of punishment, both temporally and eternally, is the real “thin blue line” that prevents a war of all against all.

The Church, it is clear, is not authorized to preach or teach any doctrine of hell other than that which is proclaimed in Scripture. The only ordinary means of salvation is faith in Christ, full stop. God will handle the rest in His infinite justice. The Church certainly cannot allow any kind of explicit universalism to be taught, even if technically possible theologically, because the Church has not been commissioned to preach it. It is a secret thing of God and not for man.

The focus of church evangelism, however, probably ought not to be the doctrine of hell. It is a cheap rhetorical trick to frighten people into believing. Belief cannot be coerced but is a symptom of a preceding change wrought internally by the Holy Spirit. It is more a turn to the light than away from darkness and feared punishment. If the desire for the good and the true in Christ is the essence of saving faith, and this conversion is a sovereign work of God, then manipulating people into faith by an undue emphasis on hell will only yield false faith and false converts, who will be choked out by the cares of this world.

St. Paul tells us that, in spiritual things, we but see through a glass darkly and undoubtedly the next revelation will differ at least as much from conventional interpretations of the New Testament as the New differs from pre-Christian conventional interpretations of the Old. Many of our doctrines will be revealed as wrong or misguided. Like the old adage about marketing spending being half-wasted but not knowing which half, it is impossible from our vantage point to determine these errors, but their likely existence provides a lot of white space for the resolution of doubts from the honest faithful.

Why Write This Essay?

Have I contradicted myself? If the church is not authorized to preach any doctrine but the Biblical doctrine, why do I write an essay that some might say is trying to find a way around the classical doctrine?

First, I am not an officer of the church, nor do I have a desire to be, ever. I have quite enough responsibility in my life without taking on additional burdens of spiritual authority. As such, I am a little more free to color outside the lines, since I have no authority to speak for the church.

Second, as mentioned above, the classical doctrine tends to be presented without full context, such as in the case of elect “Gentiles,” infants, and the mentally infirm.

But, third, if a sincere believer struggles with this issue as I have, and many do, it is dishonest to keep these discussions hush-hush as if our faith cannot handle the smallest bit of mystery and doubt. Honest questions deserve honest answers.

Tom Wolfe, in his semi-fictional novel Bonfire of the Vanities, describes, in the colorful and sometimes offensively blunt vernacular of his subjects, the yearning of NYC law enforcement for “Great White Defendants,” i.e. interesting cases with evil geniuses on the other side that present a challenge to prosecute and gave some satisfaction of punishing premeditated malevolence. Most of their cases they called “pieces of s**t,” just another low-impulse-control idiot who got violent, who wasn’t particularly evil, just dumb and hot-headed, and the depressing part of their job was putting these guilty-as-hell people away so they couldn’t hurt someone else in another toddler-like fit of rage. Wolfe explains:

Every assistant D.A. in the Bronx, from the youngest Italian just out of St. John’s Law School to the oldest Irish bureau chief, who would be somebody like Bernie Fitzgibbon, who was forty-two, shared Captain Ahab’s mania for the Great White Defendant. For a start, it was not pleasant to go through life telling yourself, ‘What I do for a living is, I pack [disproportionately minority perpetrators] off to jail’…

Not that they weren’t guilty. One thing Kramer had learned within two weeks as an assistant D.A. in the Bronx was that 95 percent of the defendants who got as far as the indictment stage, perhaps 98 percent, were truly guilty. The caseload was so overwhelming, you didn’t waste time trying to bring the marginal cases forward, unless the press was on your back. They hauled in guilt by the ton, those blue-and-orange vans out there on Walton Avenue. But the poor bastards behind the wire mesh barely deserved the term criminal, if by criminal you had in mind the romantic notion of someone who has a goal and seeks to achieve it through some desperate way outside the law. No, they were simpleminded incompetents, most of them, and they did unbelievably stupid, vile things.

Part of the reason most evangelical churches have such cringe aesthetics and huge programmatic budgets is that ambitious pastors were able to twist the arms of conservative church members (i.e. donors) to lower their standards of propriety in hopes of reaching the lost more effectively. While perhaps leading to conversions in the short term, these compromises further alienate the most influential and intelligent people in our society, which is why smart young conservatives, if they don’t leave the faith entirely, often end up in Catholicism, which still takes itself seriously enough to avoid goofy stuff like Star Wars Sunday.

Strangely, one exception in the literature is plastic surgery, which seems to make people permanently happier. The most common procedure is rhinoplasty, which is very low risk and makes a life-changing difference for those with unfortunate schnoz shapes, as humans have a large region of the brain dedicated to processing faces. There could be a spiritual connection here too since our physical deficiencies follow those of the soul; our first parents in their innocence undoubtedly had perfect aesthetics. Given this, I think we are close to the first trillion-dollar drug as weight loss peptides zero in on appetite control with tolerable side effects.

Some Calvinists like to get stingy on this and go with the Confession’s language of “elect infants,” which of course doesn’t answer the question. As one Sunday School teacher pointed out when I was a teenager, a scheme of extraordinary salvation for the young functionally equivalent to the Baptist concept of an “age of accountability” seems justified at minimum based on God’s exempting those under twenty from His judgment on who might enter the Promised land.

Further challenging free will narratives, the new weight loss drugs like Ozempic not only cure gluttony but seem to also reduce people’s propensity for addictive behavioral and substance abuse vices, including alcohol, opiates, gambling, and compulsive shopping. This raises interesting theological questions about the nature of sin and also seems to validate St. Augustine’s taxonomy in his holding that sins of the flesh as the least spiritually serious, as their treatment by medication would indicate their more superficial status among deformations of the soul. They can ruin one’s life, certainly, but are of a different quality than cold-blooded evil.

These unknowables about people’s limitations are why I also tend to be more generous with assurance of salvation — the standard had better be generous or almost all of us are screwed — and reject concepts like John MacArthur’s “lordship salvation,”, as much as I respect him. MacArthur is self-evidently a person with incredible genetics (college athlete + 99th percentile IQ), an extended phenotype of good parents, resulting in higher self-control and a less frustrating life trajectory than most, and I think he, like many who are as much blessed as virtuous, projects what comes easier for him as universal spiritual fruit rather than natural endowment.

On a much lower-stakes scale, as an employer and parent, I often should show mercy for certain infractions. However, if I pre-announced exactly what mercy was on offer under what conditions, I would cultivate more infractions. It’s clear to me that the optimal exercise of authority involves official strict standards coupled with generous but ambiguous mercy for venial mistakes.

I recall in The Godfather how the patriarch of the family, dying in a hospital, deliriously feared his coming judgment, and of course the final, haunting scene of the novel where Michael’s WASP wife found herself fully transformed into their enchanted world, veiled, like his mother, for daily mass to pray for her husband’s soul. The Corleone family was itself less evil than it could be, as an older crime family with some Old World noblesse oblige, limiting itself to gambling and various forms of theft and rackets, eschewing prostitution and drugs, which made space for newer crime families to become more profitable and powerful.

Rob Henderson notes, “Across countries, belief in a contingent afterlife that is dependent on how one behaves now is associated with greater economic productivity and less crime. The book communicates research based on data from 1965 to 1995 and found that if the percentage of people in a country who believe in hell and heaven increases by 20 percent, that country’s economy will grow an extra 10 percent over the next decade. Additionally, the greater the percentage of people in a country who believe in hell, the lower the murder rate. Intriguingly, the opposite is true for belief only in heaven: That is, the more people within a country believe in heaven but not in hell, the higher the murder rate.”

Well done. I have been fascinated by the descriptions of the last / great Judgement. It is clearly multilevel and interactive with the whole of humanity, both the righteous and unrighteous. So that it appears that the whole of the history of the world and humanity will be replayed for all to see. We shall know fully as we are fully known. The queen of the south will rise up.... A person of faith. The people of Sodom and Gomorrah will rise up .... People condemned for their sin. Every idle word, every hidden thing. The image is of the whole of humanity seeing all that is done by everyone. It also seems that we will understand all the hidden aspects of creation, how the world comes together. I think this is necessary for us to know what each person's actions flow from, what influences, and what struggles. Paul says we will judge angels. Again, our full knowledge will go to the total influences that come into their rejection of or obedience to God. This total knowledege will allow us to join in Christ's judgment of the world. Every human will understand the actual level of obedience, love, hatred, rejection for each person and angle / heavenly being. Each person will know, understand, and be in full agreement with the judgement given to them. Yes, the flames of regret will be very hot, what I could have done with what was given to me, and the reality of what I actually valued and loved. The glory that will be revealed in us will be so much better than 10 cities we cannot imagine it. Yet, no one will be jealous, or feel out of place. The doors to the New Jerusalem will always be open yet nothing evil will enter. The difference between good and evil will be open and transparent to all humanity. I think that it is impossible to understand the eternal quality of the lake of fire or of the new heavens and earth without passing first through judgement.

Thanks for this. I was surprised by how thoughtful and honest it was.