The Missing Billionaires

A Least Worst Indexing Strategy

The Missing Billionaires by Victor Haghani and James White asks a simple question. Given the incredibly large fortunes in history, why are there so few families with inherited multi-generational wealth on the Forbes 400? They cite the example of Cornelius Vanderbilt, who died as the world’s richest man in 1877, leaving everything to his heirs with no estate taxes.

Following the Vanderbilt family tree, the authors note that if the family fortune were managed according to now-well-known wealth management principles — diversification and risk management — this wealth would have grown faster than the Vanderbilt family, at least so far (and especially with smaller modern family sizes), and we should see dozens of Vanderbilt billionaires on the Forbes 400 today. In reality, the Vanderbilt fortune was dissipated by the 1960s.

Both authors have some skin in the game of this story. Haghani was a manager at LTCM, the famous quant fund that blew up in 1998, and White had a similar experience in a hedge fund. Both lost substantial portions of their own and customers’ wealth, and both appreciate that risk and overconfidence are fatal with investments.

Biased Coins and Risk Management

Life is gambling, gambling is life. I’ve always looked at life probabilistically, staring into the abyss of the unknowable, while most prefer false certainty. One of my personal mottos is “I can’t control everything, but I’m going to play the odds.” Sure, I’ll affirm that this is ultimately an illusion in a universe governed by a sovereign, omnipotent, and omniscient power. I’m a Westminster confessor, and Calvinist determinism is perhaps the most provably true church doctrine — we inhabit a universe of chaotic functions that merely appear random like a hashed password. But day to day, from the perspective of our tiny brains, things look an awful lot like a roll of the dice, and I’ll make plans based on a useful illusion rather than fooling myself that I can have any certainty about the incomprehensible whole.

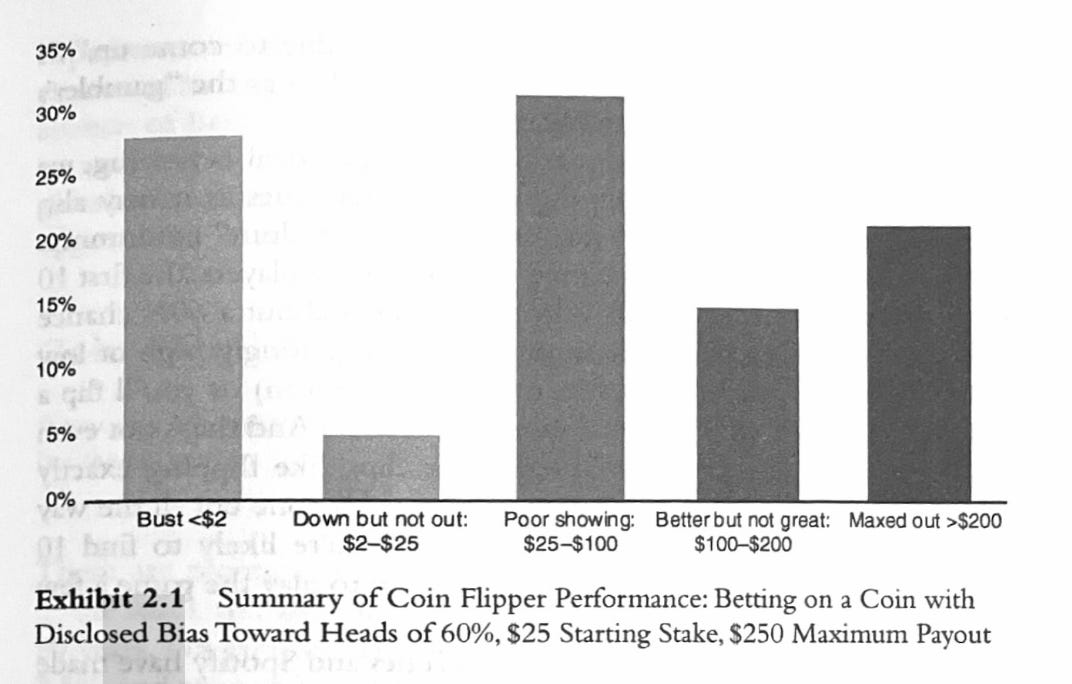

The authors of The Missing Billionaires hooked me early when they began their semi-technical treatise on personal finance by discussing bets on a biased coin flip. They conducted experiments where participants, all finance professionals, were given $100 and the opportunity to bet even money on a 60/40 coin for 30 minutes in a computer simulation — i.e. the coin would come up heads 60% of the time, and they would win or lose what they risked on each bet. To control costs, they told participants there was an undisclosed cap ($200) to their winnings, and if they hit this before 30 minutes, the program would end and they would receive the maximum payoff. They could bet any amount, up to their current bankroll, on the next coin flip. The authors were curious if financial professionals had enough basic literacy in risk management to take advantage of this favorable setup. You can try the game yourself here.

So how did the “wealth management” professionals fare? According to the authors:

Of the 61 subjects, 18 subjects bet their entire bankroll on one flip at least once, which increased the probability of ruin from close to 0% using a constant fractional strategy to 40% if their all-in bet was on heads, or 60% if they bet it all on tails, which, amazingly, some of them did. The average bet size across all subjects was 15% of their bankroll at each flip, but the betting patterns were generally very erratic, with individuals betting too small and then too big, or vice versa. Betting patterns and post-experiment interviews revealed that quite a few participants felt that some sort of doubling down betting strategy was optimal. Another approach followed by a number of subjects was to bet small and constant wagers, apparently trying to reduce the probability of ruin and maximize the probability of ending up a winner.

We observed 67% of the subjects betting on tails at some point during the experiment. Betting on tails once or twice could potentially be attributed to curiosity about the game, but 48% of the players bet on tails more than five times in the game. It is possible that some of these subjects questioned whether the coin truly had a 60% bias toward heads- but that hypothesis is not supported by the fact that, within the subset of 13 subjects who bet on tails more than 25% of the time, we found they were more likely to make that bet right after the arrival of a string of heads.

The ideal strategy in such situations is constant percentage betting, specifically the Kelly criterion, a formula deriving from information theory well-known to professional gamblers that also happens to specify the ideal amount of money to bet when one has an advantage over the house. For even money payoffs, the “Kelly” sized bet is simply the odds of winning minus the odds of losing, so for our 60% coin, this is 0.6 - 0.4 = 0.2, or 20% of the bankroll on each 60/40 even-money bet. The Kelly bet is mathematically certain, on average across repeated trials, to grow wealth the fastest on a percentage basis. In practice, most professional gamblers bet “half Kelly,” or 10% in this scenario, and indeed when most people are shown the matrix of outcomes, good and bad, they are most comfortable giving up a relatively small amount of return to smooth out runs of bad luck. The full Kelly betting level is optimal in the same way a stripped-down Corvette with a roll cage and no passenger seat is optimal.

Amazingly, almost none of the finance pros tested had heard of the Kelly formula. What’s clear from the experiment is that most wealth management professionals, like most other professionals, are careerists with low levels of intellectual curiosity compared to chain-smoking blackjack card counters. They’re smart enough to input a few parameters for “financial planning” software that spits out pretty reports. Since most of their clients are highly irrational, the main way they earn their fees is by keeping clients from doing really dumb things like selling at the bottom or going all-in at the top. They operate according to semi-reasonable rules of thumb concerning asset allocation (100 minus your age for stocks/bonds) and retirement consumption (the 4% rule).

A More Rational Way to Index

The authors propose a more rational way of allocating assets, while, and this is critical, endorsing the Efficient Market Hypothesis. While I am not an adherent of EMH, it’s probably good advice for most investors to believe it’s true, as it’s really hard to beat, after adjusting for risk and fees, a very low-cost index fund or ETF. I get the feeling the authors aren’t strict EMH believers either, but as we all know being branded a “denier” of received wisdom is harmful to credibility and influence in many fields. They instead propose a novel solution that solves the worst problem of EMH, which is its indifference to risk relative to valuations.

The authors admit that the market is efficient as far as it goes, and eschew individual stock picking as too risky, but propose that the subjective allocation of an investor can vary depending on what the market is offering. They propose a simple dynamic allocation model based on the Merton share, which modifies risk-taking according to the declining marginal utility of wealth rather than its absolute level. The most basic form of declining marginal utility is considering wealth’s utility as proportional to its logarithm so that every doubling of wealth is seen as equal to previous doublings on a linear scale. To make the math easy, we can use log base 10, which would say that $1 million in wealth is equal to 6, while $100,000 is equal to 5, so that $1 million, while mathematically ten times $100,000, has an additional utility of only 20% (6/5).

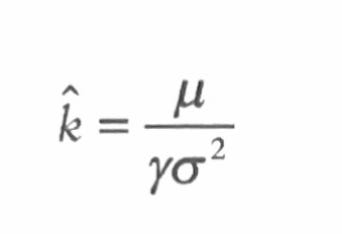

When adjusted for utility, a new equation emerges called the Merton share, an elegant expression that looks like this in simplified form:

where k is the percentage of bankroll to bet, mu is the excess return of the bet over the risk-free alternative, gamma is a personal degree of risk aversion (where 1 is risk-neutral, values less than 1 are risk-preferenced, and greater than 1 are risk-averse), and sigma is the standard deviation of returns.

Pleasingly, and though coming at the problem from a completely different angle, this equation simplifies to the Kelly criterion for win-or-lose bets like the 60/40 coin flip experiment described above. In that case, mu is 0.2, gamma is 1 for risk-neutral wealth maximization, and sigma is 1 in a binary outcome. Interestingly, the authors have found, in working with investors on risk tolerance calibration, that the median risk aversion value for typical investors is 2, which is exactly the half-Kelly bet size that gamblers have independently converged upon in real-life betting situations!

So how do the authors generalize from all-or-nothing gambling bets to the smoother returns of the stock market?

The authors define mu as the return over the risk-free alternative, i.e. the current real return on inflation-linked TIPS bonds. As I write this, for example, the TIPS yield is 2.2%, that is, it pays a coupon of 2.2% plus CPI.

To determine the stock market’s expected return, the authors reject simply assuming 6-7% in all market environments. Rather, they rely on the extensive academic research showing that the return of the market, over long periods, is simply the cyclically adjusted earnings yield. This is the inverse of the CAPE ratio, which is a modified form of the P/E metric that averages the last ten years of earnings for its denominator. As I write, for example, the CAPE ratio is 30.86 for the S&P 500. The reciprocal of this is 3.2%, which is the expected real return of the stock market if held over a long ~20+ year period.

The authors assume a historical standard deviation of 20% for the market, and assuming the typical risk aversion of 2, solving the equation we get, k = (0.032 - 0.022) / (2 * 0.2^2) = 12.5%. So given the current market’s high pricing levels and relatively attractive risk-free alternative, this approach would allocate 12.5% to stocks and 87.5% to TIPS securities. If the stock market got cheaper, or the TIPS yield were to fall, the portfolio would be rebalanced to favor stocks. Here’s how it would have allocated historically through 2022:

Note how it reduced exposure either totally or significantly before both the 2000 and 2008 crashes, and quickly re-invested once pricing became more attractive.

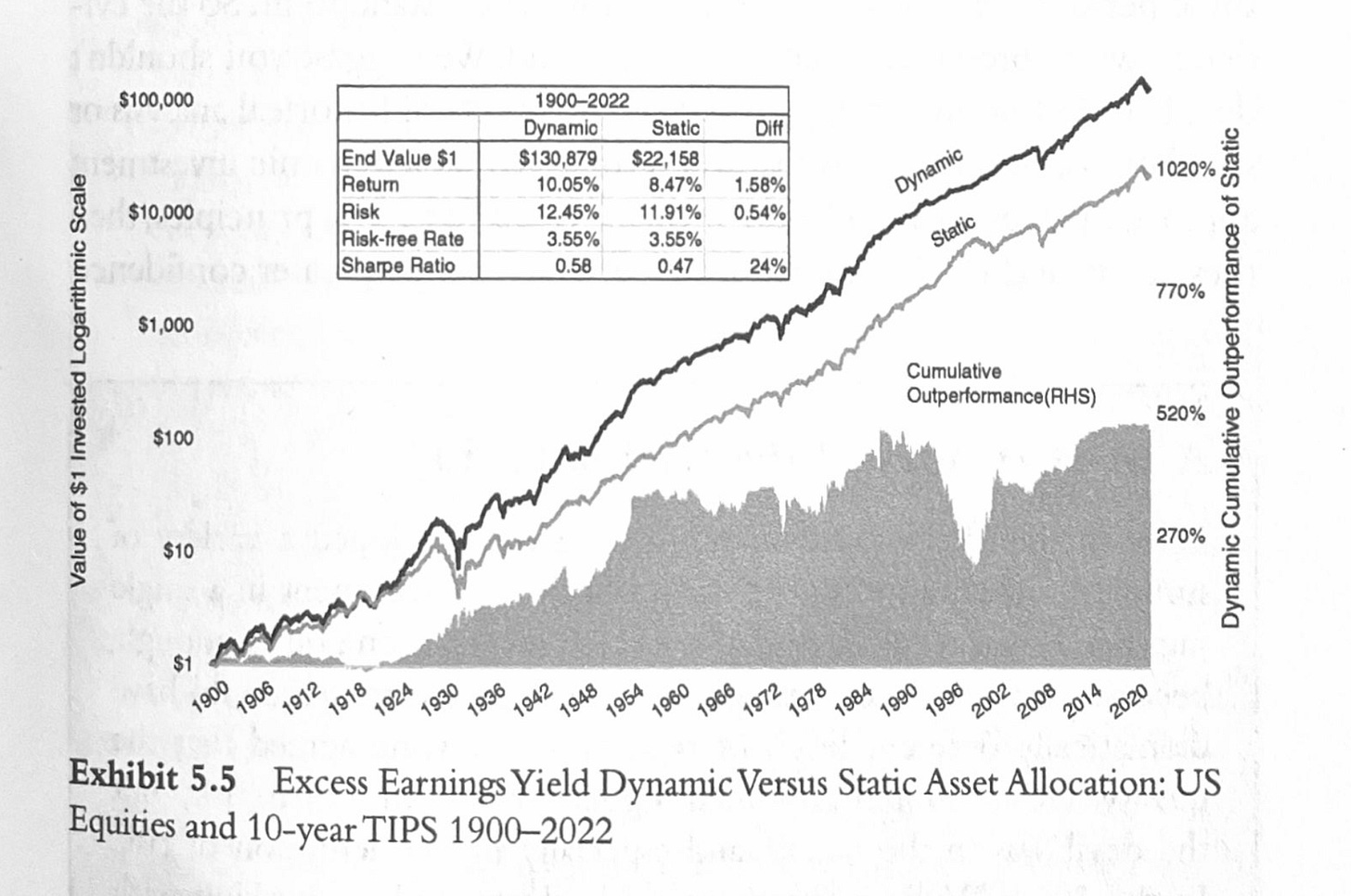

The authors present a historical backtest of the strategy showing its superiority to a 60/40 portfolio:

Further, because the strategy avoids complete exposure to the market and minimizes it during times of low expected future return, its results are more robust to “fat tails” outcomes like the 2000 crash, meaning the risk estimate as expressed by market standard deviation is itself more effective and rational. When the stock market offers an attractive return, it is better behaved and more normally distributed in its pricing.

Critiques and Comments

There’s much more to the book, notably on controlling spending relative to wealth, especially when returns are low and multiples are high. Essentially, the authors recommend never spending more than the real yield of the portfolio. They recommend we return to the financial world of Jane Austen, where people measured wealth based on income, like Mr. Darcy’s 10,000 pounds per year, rather than an arbitrary percentage of what Mr. Market thinks our holdings are worth today. The authors also note that just keeping up with inflation is unlikely to be satisfactory to most of us, as the world gets wealthier over time. The average income in 1900, for example, is about $5,000 per year in today’s money. As a result, some income must be reinvested annually to combat these hedonic adjustments to wealth.

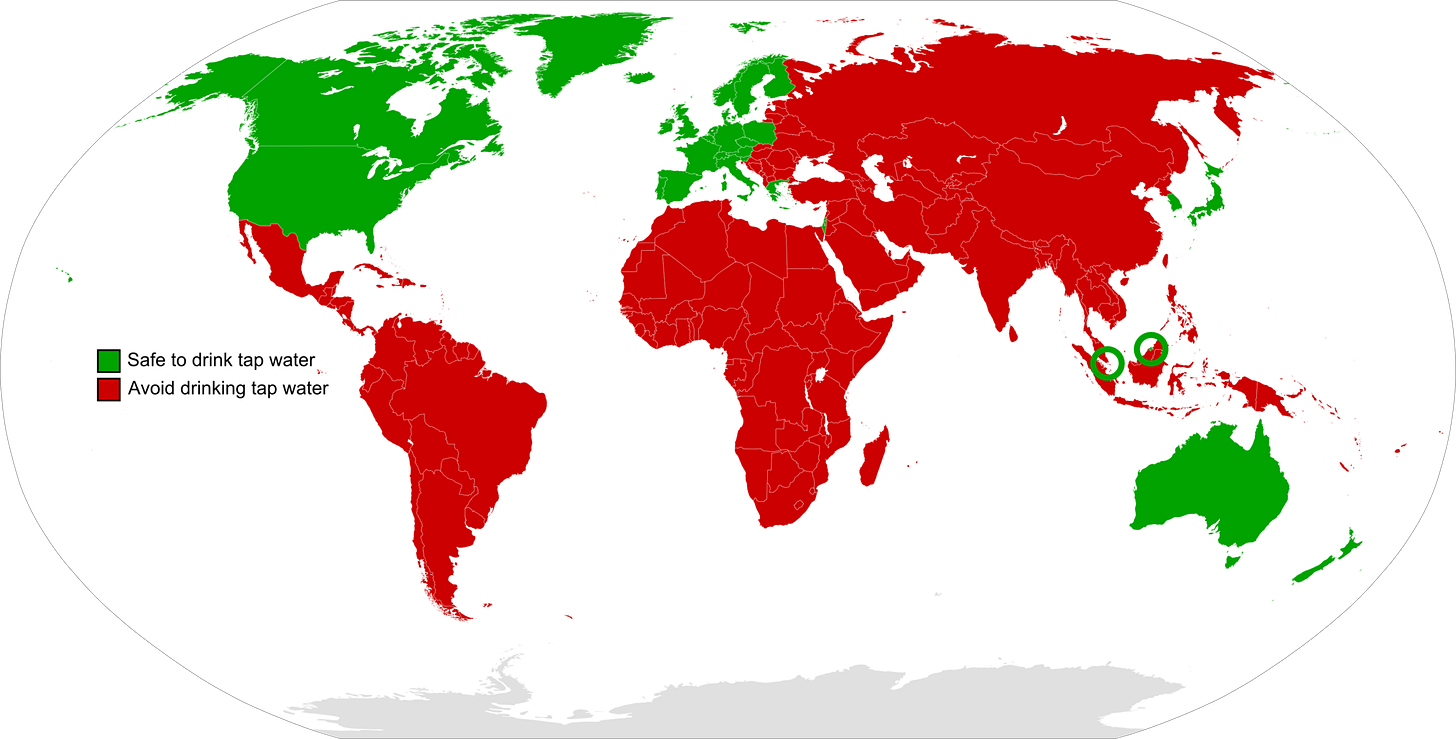

The authors recommend using a global index for the stock market portion of the portfolio, though I’m skeptical this is a net benefit. My financial advisor has a simple rule that we don’t invest in countries where the culture and social capital is retrograde enough that you can’t drink the water according to the CDC:

Like in Sid Meier’s Civilization, aqueducts or the equivalent come before stock exchanges. If a country won’t or can’t invest in century-old technology to save its own population from preventable infectious disease, theoretical property rights in a stock market share are probably suspect. Once investments are limited on this basis, any index is statistically similar to US stocks anyway on a market-capitalization basis.

Their approach reminds me of the Permanent Portfolio, which allocates 25% each to stocks, long-term bonds, gold, and t-bills, with not-quite-annual rebalancing, that has historically outperformed traditional portfolios. All approaches that rebalance, especially in less correlated assets, benefit from systematically buying cheaper things and selling more expensive things, juicing returns and reducing risks from crashes. The authors’ is an approach to indexing that takes advantage of Shannon’s demon but does so with at least a rational assessment of expected returns and risk.

Just when I was on-board with their approach, the authors further enhance returns by incorporating an undisclosed momentum measure (presumably some sort of short/long moving average crossover) that causes them to allocate up to 30% (!) more to stocks (though never exceeding 100%, i.e. no leverage ever), regardless of expected return, when they’re going up, and this both enhances return and lowers risk. This of course undermines their purported belief in efficient markets and makes them just another gambler with a hot hand.

I believe that the historical success of momentum approaches and heavy indexation makes the market extremely prone to fast crashes like we saw in 2020 post-Covid. It seems extremely dangerous to take on extra risk on the assumption you’ll be faster to the exits than everyone else based on a backtest everyone already knows about.

I fundamentally cannot leave the rational world of Buffett-style value investing. That is, I should only want to buy shares of businesses where I would want to own the entire underlying business at the current market capitalization. To invest based on capitalization of an index — where the authors admit that prices are three times more volatile than the underlying earnings that long-run justify those prices — strikes me as a systemic risk.

All that said, effective value investing is very difficult, emotionally and analytically. I am satisficed enough with the authors’ approach that I would heartily recommend them to others as a default option, as compared to standard wealth management. Their firm, Elm Wealth, charges very low fees and publishes their target allocations. Admittedly, their proprietary approach is less pure that the risk-on/risk-free asset dichotomy presented in the book, but this may be their solution to a marketing problem. They probably need to complicate the portfolio a bit, because investors generally don’t like paying fees during those times where, in theory, it pays to sit in TIPS with 87.5% of the portfolio.

Answering the Missing Billionaire Question

The authors do not return to the question they originally posed. Why did families like the Vanderbilts go from shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in a single century? The answer is likely multi-faceted.

First, neither highly diversified investment products nor research on the historical returns of those investments was yet available in the 1800s. Second, we have hindsight bias, in that America was an extremely lucky country; we were entering the American Century and our stock market returns were phenomenal, but no one could easily know that in advance. We would never, as Fehrenbach put it in Lone Star, commit the unpardonable sin of losing a major war. There is perhaps no country in history with America’s capability and confidence, and the latter so important in business — as Norm MacDonald put it, “It says here in this history book that luckily, the good guys have won every single time. What are the odds?”

Third, it is often the case that inherited wealth is a burden. It can create a sense of guilt or an inferiority complex in the recipient. I would be curious to compare family wealth dynasties from 1750-1850 to those from 1850-1950. The decline in sincere religious faith, especially among the elite, I speculate, made it harder for families to both handle the emotional weight of extraordinary Providence and maintain the self-control necessary to preserve it.

So what is the solution for multi-generational wealth preservation? I wish I knew, but I’ll present my best guesses:

First-generation wealth must demonstrate an appropriate level of humbleness. They must acknowledge the undeniable role luck plays in the fortunes of men. This places less of a burden on the second generation to “prove” themselves by taking risks, engaging in performative displays of purity such as left-wing activism, or else wasting their lives in dissipation. It’s a much easier burden if the first generation can say, “We’re all lucky because I didn’t earn this entirely on my own.”

Humbleness also means seeing oneself as a steward, not an owner. Assets are held in trust for the family, not one’s own playthings to liquidate, risk, or donate. Imagine being Buffett’s or Bill Gates’ children, grown adults whose parents don’t think they’re worthy of inheriting their fortunes. “It’s ok for me, but not for thee.” Pure egoism.

In acknowledging luck, there ought to be healthy risk aversion in choosing investments to diversify outside the family’s core competencies. This would also advise against selling a family business, as investing a large amount of cash all at once concentrates risk on that moment’s available investments and the investor’s relative lack of knowledge outside of his or her native field of expertise. Better to take annual distributions from a cash cow business, dollar-cost-average those into healthy single-digit real returns in a diversified portfolio with a real margin of safety, spend a bit less than this yield, reinvest the rest, sleep well at night, be right, sit tight, letting compound interest do the work.

Start distributing significant income from these investments to virtuous heirs when they are adults raising kids, not after the first generation dies. Let them “test drive” managing their own funds before they get access to the nut, and when utility is maximized. If they’re gainfully employed, a supplemental $40,000 a year for a young married couple is much more useful to them than an inheritance when they have gray hair.

Give the heirs something to do. Franchise businesses, for example, are arguably “buying someone a job,” but there’s value in work and independence, and the opportunity for outsized rewards based on value provided.

If possible, and the family culture is healthy enough to allow it, appoint a single, virtuous successor to manage the family’s assets. Share everyday decision-making (and appropriate executive compensation) by age 70 or preferably sooner, and consider older grandchildren in their 30s if they’re around. Like a relay race, the founder should want to run alongside the successor as long as possible to ensure a seamless transition. One can’t control things from the grave, or trust outside managers unilaterally, so appoint the best family successor possible.

As the authors demonstrate from history, preserving a fortune for the long-term is a hard problem. Those lucky enough to face this problem need luck yet again to pull it off.

I have to echo, great review!

Concerning first-generation wealth and staying humble as you wrote in conclusion, I humbly submit this applies equally on an individual level.

This is especially true for first-decade wealth. Whether dot-com stocks, house-flipping, crypto coins and NFTs (lmao), or meme stocks, it appears the new normal in our post-scarcity economy and financial system is an endless series of bubbles. For a variety of reasons 20-somethings are especially likely to catch these on the way up, but not fully realize the forces at work. So instead of taking their windfall and living happily ever after, they inevitably try to parlay it into more using the same playbook, not realizing they were simply lucky to be in the right place at the right time and caught lightening in a bottle.

Nor does it stop being a warning just because you are in your 40's or 50's, or even 60's and 70's.

The only thing one can do is stay humble and recognize when you as an individual *have enough.* Once you are humble enough to feel you have enough, and humble enough to realize you're not perfect and aren't going to win every time, or most probably your last time, it's easier to switch your method and your mindset from building wealth to preserving wealth.

Again, great post and great substack. Thank you.

Great review!

I have Missing Billionaires in my stack to read, although I have only skimmed it and examined the index in writing up these thoughts:

The authors mention the Vanderbilts, but not the Marble House in Rhode Island (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marble_House), which was built by a woman who married the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt. It cost $11 million in 1892, at a time when an ounce of gold was equivalent to $20. (Most of the expense was for 500,000 cubic feet of marble.) A mindbogglingly large figure, it would be $1.1 billion today in gold terms or $17 billion if looked at as a percentage of GDP.

The Vanderbilt story is in a book called "Fortune's Children," which a descendant (Arthur T Vanderbilt II) wrote in 1989 to answer the question frequently asked of him, "why aren't you rich?" The answer is that the descendants of Cornelius, starting with his grandchildren, spent the money extremely rapidly, largely on houses.

The Vanderbilt experience would tend to show that extravagant spending is a key part of the explanation for the missing billionaires. The psychology - mistakes and delusions - of these elite WASPs at the turn of the century is also a window into how founding stock Americans lost their country.

Don't worry about leaving too much money to your descendants because the odds are that they will waste it. Try to leave them good genes and culture. And note that it was the spouses that married into the Vanderbilt family that were responsible for much of the extravagance and waste. Would you be surprised to hear that the builder of the Marble House was a suffragette, and that she later divorced her husband?

The other keys to the puzzle, which the authors don't seem to address, are the confiscatory levels of estate and income taxation during the 20th century from the time that FDR was elected in 1933 until the late 1980s. From 1941 through 1976, the top estate tax rate was never less than 77% and the top bracket was only $10 million. From 1977 through 1981, the top rate was 70% on amounts above $5 million.

The reason that we have the Ford Foundation today is because the Fords had to either do that or hand over their company to the government when Henry Ford died in 1947. And remember that the Fords had bought out all of the minority shareholders of Ford in 1919 for $105 million. If they had been allowed to keep their company, Ford descendants might today still own all of a $40 billion company.

Also consider the investments that the Vanderbilts could have been making during a period of technological explosion if they'd had that $11 million instead of spending it on marble. (https://www.amazon.com/Transforming-Twentieth-Century-Innovations-Consequences/dp/0195168755/) The period between 1900 and 1910 saw the founding of Ford, General Motors, Hershey Chocolate, Harley-Davidson, Pepsi-Cola, Texaco, J.C. Penney, Quaker Oats, and Firestone Tire and Rubber. When Ben Graham started investing in 1916, IBM (then known as CTR, Computer-Tabulating-Recording Co) had a 7% dividend yield, traded at one-third of book value, and less than ten times earnings.

Meanwhile, the top bracket income tax was 91% from 1946 through 1963. The post-war high marginal income tax rates coincided with a period of high inflation, and high income tax and high inflation operate in concert as a wealth tax.

I'm puzzled that the authors think there is a missing billionaire puzzle. The simplest explanation is that the wealth is dissipated by extravagant spending by the heirs and by taxation. During the 20th century, extremely wealthy individuals were barely able to maintain their fortunes during their lifetimes because of the income tax that functioned as a wealth tax, and then the government confiscated almost everything else after they died.