One of the dangers of public writing is that you can be held accountable for predictions, which are always difficult. In my early 2022 post, I predicted the following:

My specific economic predictions for 2022 are:

Shrinking corporate profit margins, especially for non-essential goods. This is currently not happening, so we would need to see a change in this trend.

Wage growth continues to lag inflation substantially, especially in the white-collar portion of the economy. This is already happening, so I predict this trend to continue.

Huge profit growth for basic industries, especially the most irrationally disfavored and essential one, fossil fuels. I’m super excited about some of my own investments given the 20% cash flow yields of some oil producers while oil consumption is nearly recovered to pre-pandemic levels. This is particularly true if Omicron turns out to be nature’s vaccine.

So how did I do? My first prediction turned out to be early or mixed. Most retailers, like Wal-mart, are indeed seeing lower margins, and margins are declining in the S&P 500. Aggregate economic data, however, suggest margins probably peaked sometime in 2022. I’d tend to trust the S&P 500 data more than gross economic statistics, which can be subject to reporting delays and other statistical anomalies. That S&P margins shrunk despite the accounting chicanery the often goes into earnings reports tells me I was right. Companies have a lot of latitude to distort their margins and earnings, and if they report lower numbers it’s probably an indicator that the real number is actually worse.

My second prediction also worked out. Wage growth peaked at 6.4% while inflation was somewhere around 7.5%. White collar and higher paid workers saw lower wage growth and a significant reduction in purchasing power.

My third prediction about the energy sector also seems to have happened. The energy portion of the S&P reported huge growth, and more than covered the entire growth of corporate profits in 2022. Without energy, the S&P would have seen profits go down about 5%, and this while inflation is at 7%, resulting in a real decline of 12%. This is amazing given the massive glut of oil during the year as the government sold down the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to soften the impact of inflation running up to the midterms.

What’s most interesting about these developments is how no workers actually had a net wage increase relative to inflation. Wages are sticky and take some time to adjust, but the demand for “unskilled” service workers has been strong and robust for over two years now due to the pandemic. I just finished reading The Great Demographic Reversal by Charles Goodhart* and a coauthor, which predicts rising wages to workers (net inflation), higher interest rates, and higher inflation. The book argues the following:

*Goodhart is one of my favorite economic thinkers because of “Goodhart’s Law,” which states when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. This is because people will take shortcuts to artificially boost the measure once they know it’s being tracked. One of my “laws” of business is that managers should have measures they track, but keep them secret, only using the measure to trigger deeper investigation into possible problems.

Returns to capital were elevated from 1995-2020 due to a one-time glut of labor relative to capital. As large post-WWII generations in developed countries came of age, but didn’t have many children relative to their parents, the number of workers relative to non-workers (children and elderly) rose, making societies temporarily richer but returning most of that excess to the wealthy who provided capital, increasing inequality. At the same time, huge swaths of humanity with high economic potential but defective Communist governmental systems for much of the 20th century entered global markets. Most notably, China, and to a lesser degree, Eastern Europe. Since North Korea remains as the last “hard Communist” state, and birth rates are collapsing in all of the advanced and developed economies, there is no future supply of new labor to continue this trend.

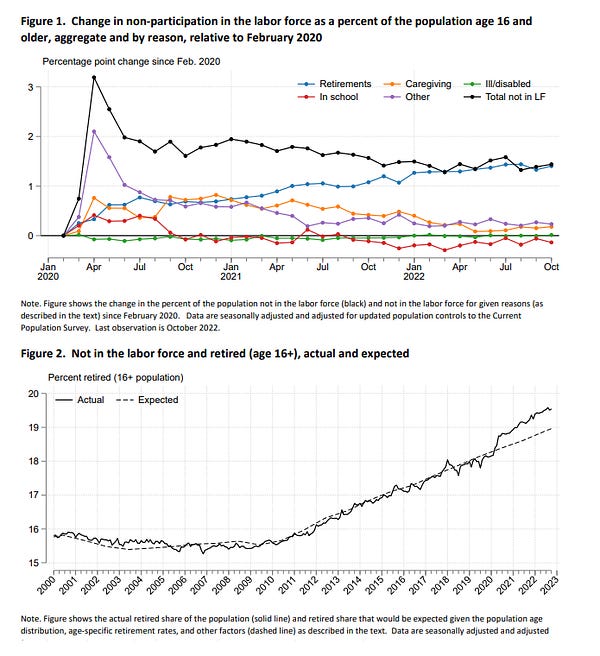

As the population of global workers ages, and life expectancy increases, the number of non-workers, i.e. the elderly, will increase. They will no longer be earning money or contributing economically, and so will be spending money they have saved or receive from pension benefits. In addition, since medicine has advanced in keeping people alive, but has not advanced significantly in treating dementia, more and more elderly will be living longer with the need for intense, expensive care in their later years. Fewer people dying of heart disease in their 60s means more people in their 80s who will need labor-intensive care that cannot be easily automated or outsourced to lower wage economies. The Federal Reserve recently conducted a study showing that the post-Covid shortage of workers is at about half explained by natural aging of the population that would have happened from 2020 until today (excess mortality from Covid and/or vaccine side effects may also be a contributor - this is hard to untangle because the deadlier Delta variant coincided with the rollout of vaccines, but the continued excess mortality among healthy working-age people with group life insurance plans throughout much of 2022 would seem to point to at least some effect of the vaccines*).

* This is all still really hazy. One analysis focusing on the most trustworthy statistic, excess mortality, showed that many advanced economies with high vaccination rates had lower overall mortality from 2020-2022, whereas the US and a few other advanced economies showed higher. The author concludes that a) the vaccines themselves had little effect on mortality but were only somewhat effective at preventing deaths and did nothing to slow the spread or prevent infections and b) excess mortality was largely explained by higher obesity rates in the US and other countries showing excess mortality, which makes any Covid infection, vaccinated or not, more fatal and debilitating, whether the person dies immediately or later from accumulated damage after the infection.

While the headline here focuses on early retirements (which may reverse if the stock market continues declining), the study itself shows that the other half of the decline in workers is due to aging. We just happened to have a pandemic at the same time large cohorts of the Baby Boomer generation were going to start exiting the workforce anyway:

This will have a double effect on inflation and wages. At the same time fewer goods and services are being produced by the shrinking pool of workers, more money will be chasing those same goods and services as the elderly spend their savings and pension benefits. The net result should be high inflation and even higher wages for workers.

As the savings of the elderly are spent on current needs, there will be a lower supply of savings for investment. At the same time, with rising wages businesses will again be looking to spend money on technology and other improvements to make their workforce more efficient, i.e. to get more done with machines and information systems with fewer of the shrinking pool of workers. Think about a McDonald’s restaurant. If the natural wage of fast food workers rises to 20% of sales versus 10% of sales, it becomes much more profitable to invest in robots or other labor saving innovations to reduce the need for workers. Most of the time, companies borrow money to make these improvements. But, if the supply of investment dollars is lower due to savings being spent by the elderly, interest rates should rise as well. More businesses will want to borrow money to make investments to reduce their need for higher-wage workers, but less money will be available to borrow, raising the price of money, i.e. interest rates.

The are two X factors that could interrupt these trends: technology and the remaining growing demographic groups in India and Africa. First, technology could vastly increase output. The authors are skeptical. First, productivity in services (say home health or physical therapy), which are most needed by the elderly, are least conducive to robots or computers making them more efficient. Office workers, for example, who essentially provide services, are not significantly more productive today than they were in the 1990s, despite massive technological change in the office environment, and productivity growth overall is slowing or even declining despite supposedly groundbreaking technological progress. While there is increasing excitement about automation, manufacturers have been using robots since the 1970s to reduce labor costs with repetitive processes; many of those most obvious gains have already been captured. General purpose robots to automate more complex and uncommon tasks that workers currently perform are a big unknown, and if their development is anything like the hype surrounding “autonomous” vehicles, it will be many years before they could possibly make a dent in services demand.

The other X factors are India and Africa, which still have growing populations. The authors are careful in how they address this, but they imply that there may be cultural limitations to full integration into the global economy relative to the effect of China. China was the world’s largest economy and most advanced civilization for most of world history, and was artificially kneecapped by Communist economic practice. Once that ended, China rapidly regained its former status as an advanced economy of industrious workers. That is unlikely to happen as quickly with Africa and India according to the authors. India has had free markets for longer than China, but has struggled to reach Chinese levels of productivity, and its population growth is slowing rapidly. Africa, on the other hand, is less developed and its population will grow for at least the remainder of this century. One thing that occurred to me is that it seems possible that China, not hindered by post-Christian Western guilt over colonialism, may simply colonize Africa themselves, as a global shortage of workers will present a massive economic opportunity to “organize” Africa’s growing population into more productive labor. They are already entering into development contracts involving debt with many African countries, and operating raw material mining operations with African workers that are essential to Chinese manufacturing. Should one of those countries default on the debt, or endanger Chinese property rights on the continent, I could see China sending security forces to enforce their interests, which could lead to the Chinese enforcing coercive regimes on African workers, i.e. a form of slavery, at least as harsh as those operating in China today among their own people. I do not see them abandoning their economic interests over moral qualms like the British abandoned Rhodesia and South Africa. It may turn out that the natural equilibrium in this fallen world between cultures of vastly different baseline productivity is some sort of colonialism.

So that is the case for increased wages, interest rates, and inflation from The Great Demographic Reversal, and I don’t substantially disagree with their arguments. However, the question remains unanswered as to why worker’s wages are not exceeding inflation.

My best explanation for this is that macroeconomics does not adequately account for worker quality. Productive work in an advanced economy requires something like a Protestant work ethic, at least culturally. As the founder of Home Depot recently put it, “I can tell you right now, after some meetings I had yesterday, you can't hire people. They don't want to work. Nobody wants to work anymore, especially office people. They want to work three days a week. It's incredible. How do you have a recession when you have people that don't want jobs? They're entitled, they're given everything. The government, in many cases, if you don't work, you get as much money as when you did work… And so you get this laziness, which you have, and it's basically a socialistic society.”

Goodhart and his co-author, like all macroeconomists, can only have tidy theories if workers are all the same. That is, they must assume the people who are already working are pretty much the same as the people who aren’t working. So, if employers offer more wages, more workers who aren’t working will be motivated to work and they can plug into the economy as any other worker. I’m afraid this isn’t the case.

Imagine you’re the poor manager of an Olive Garden, desperate for workers post-pandemic. You’ve been able to raise prices a bit, but you’ve had to raise wages more since these are low-paying jobs. Let’s say you need someone to prep salad bowls, and whereas before you were paying $12 per hour you up the wages to $15 an hour. This catches the attention of a young man who is unemployed and you’re desperate so you hire him. You, as the manager, need this guy to prep one salad bowl every 5 minutes inclusive of lunch and breaks. The worker you hired, though, is a pothead whose previous “employment” was playing video games all day in his parent’s spare bedroom. Every time you go to check on him, he’s behind on his task, playing some dumb game on his phone or texting his dumb friends. He manages to prep, badly and not at all to specification, about one salad bowl every 15 minutes, and acts like you’re the one with the problem for expecting him to stay on-task the entire time he’s clocked in. In a couple of days, you let him go because he’s costing more in productivity (with customer complaints, lowered morale from his more productive coworkers, and management effort) than he creates. This “worker” brings negative economic value to the business at any wage. He is unemployable for reasons an employer cannot fix, and indeed cannot be fixed except by totalitarian means, i.e. some sort of involuntary boot camp experience to teach the young man the discipline and respect he failed to pick up starting as a toddler.

This leaves Olive Garden in quite a pickle. They can continue raising wages and prices, but as they raise wages what they find is that they are pulling productive workers not from the unemployed, but from other productive businesses. And there comes a point where the customer is only willing to pay so much for warmed over breadsticks and iceberg lettuce slathered in seed oil. The consumer has a choice, which is to prepare better food for less at home, with about the same time it takes to drive to a restaurant and wait for a mediocre experience. I’ve certainly noticed the decline in quality in almost every mass-market restaurant I patronize. They want you to pay more for less - a Jason’s Deli muffuletta has about half the meat it used to - and then expect you to “tip” on top of that for a fast casual experience.

Contra Goodhart, I do not think higher wages will entice enough employable workers out of unemployment to raise output enough to have a true rise in wages relative to inflation. Inflation is the natural signal that we are all, on average, getting poorer because at the margin there are fewer workers making fewer things and providing fewer services. People will have to accept this, as workers aren’t an infinitely elastic supply with much of society so morally degenerated they can’t be employed.

Most likely, the government will find a way to cook the CPI numbers to limit the growth of entitlements. At the margin, one of the engines of capitalism, the division and specialization of labor, will start to recede. Those who work at the most abstract layer, in offices processing information, will contract in both real wages and numbers, while workers doing the most necessary physical work will be the only ones who just barely keep up with inflation. We see this already in the economic numbers. With inflation at 7.5%, those in the bottom quartile making less than $18 an hour saw wage growth of 7.4%. Those who work in offices saw wage growth of less than 5%, effectively taking a 2.5% pay cut. Long-term, costs to care for the elderly will be controlled by the shortage of workers. Nominally, they will be cared for, but will be increasingly neglected except by families with the means to provide private care, paid or unpaid.

Note these are average predictions. If you can raise disciplined kids who work hard, they should do really well over the next few decades, and a large family is likely the best social insurance against neglect and loneliness in old age. Children, among the virtuous, will again be the best investment.

That leads to my economic predictions for the year, which are largely the same as last year:

Corporate margins will continue to compress indicating the relative power of labor over capital in a shrinking employable population.

Inflation will slow and the Fed will stop raising rates sometime this year. If they start cutting, inflation will pick up again, somewhat slowly, and we will eventually have a double top in inflation like in the 1970’s. This will become noticeable sometime in 2024.

Basic economic players, like energy, will outperform more abstract sectors like tech, both in earnings and likely to a larger degree in stock market returns.

Wages at the bottom may exceed inflation, but we’ve yet to see it.

That’s all for now, hope everyone has a prosperous 2023, for we live in interesting times!